“If I don't die young, I hope to live as a great artist. But if I die young, I intend to have my diary published. It cannot fail to be interesting.” These are the words of Maria Bashkirtseva, a gifted Ukrainian painter, sculptor, writer and emancipation activist, six months before she passed away aged 25.

She was born on Nov. 23, 1858 in the village of Havrontsi near Poltava, central Ukraine, into a family of rich landowners. When she was four, her parents divorced and she lived with her mother and younger brother in her mother's native village of Cherniakivka, some two dozen miles away from Havrontsi. There, everyone doted on her, and two governesses taught her foreign languages, the piano and drawing.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

When Maria turned 12, her younger brother went to live with their father while she stayed with her mother. Soon afterwards, they left for Vienna, then lived in Baden-Baden, Nice, London, Berlin, Brussels, Madrid and other European cities.

Although it was difficult for Maria to get used to the constant change of environment, she continued to learn to play music, sing and paint. Nine hours a day, she learned school subjects according to her own curriculum and successfully completed a three-year gymnasium course in five months.

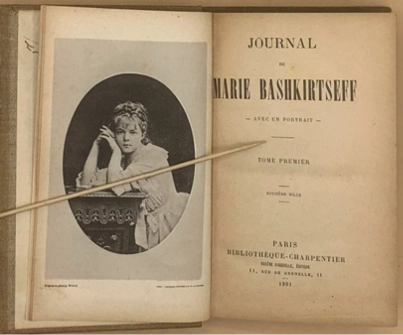

It was then that she began to write what would later become her famous “Diary” (or “Journal”). Originally written in French and completed in 1884, it was posthumously published in several languages and described as “a strikingly modern self-portrait of the gifted adolescent mind.”

Michael Kmit: the Ukrainian Who Helped Redefine Contemporary Art in Australia

It was praised by Anatole France and Emile Zola. In 1890, then British prime minister William Gladstone called Maria’s Diary “one of the most prominent books of the 19th century.”

Maria’s Diary vividly and earnestly reflects the inner world of a young girl who seeks recognition and acclaim but knows that her years are likely to be cut short, hence is keen to make the most of them.

In an almost novelistic description of the contemporary European bourgeois environment, the author reaches deep into the nature and manifestations of joy and sorrow, good and evil, empathy and envy, trust and deceit, love and malice.

In 1873, Maria and her mother moved to Paris where the teenage Ukrainian beauty got caught up in the whirlpool of beau monde routs, receptions and soirees. She had a beautiful voice and wanted to be a singer. She spent hours taking lessons of singing and music, but one day she lost her voice.

Posthumous edition of Maria Bashkirtseva’s Diary, 1887

The cause was one of the early symptoms of tuberculosis, which ran in the family, and sadly got worse from month to month. Maria felt weaker and weaker and fainting episodes occurred more and more often. No medications helped to deter the progressing disease, so doctors advised her mother to take her to Italy.

There, she would spend days in picture galleries. Inspired by canvasses of Titian, Rubens, Van Dijk and other great artists, Maria decided to take painting lessons. In one of the first lessons, she managed to paint a beautiful portrait in 90 minutes.

She wrote about it later: “I'm satisfied with myself, and if I say so, it means I deserve it. I'm a scrupulous type and I'm hardly ever satisfied with anything, especially myself.”

In Rome, Maria fell in love with Cardinal Antonelli's nephew Pietro while her heart was sought by count Vincenzo Bruschetti. She married neither, though she touchingly described that emotional experience in her Diary.

In 1876, Maria traveled to her homeland where she stayed at Poltava mansions and estates and visited her father. She tried to reconcile her parents but failed and returned broken-hearted to France.

Decision to become a painter

In Paris, Maria firmly decided upon being a painter. She wrote: “This is not a temporal but final decision. If painting doesn't make me famous soon, I'll kill myself and that's it. It's been decided since months ago.”

She was admitted to Julien's Studio, the private art school known for numerous famous alumni. A very diligent student, she enthusiastically mastered techniques and subtleties of the art, and after six months caught up with the school's best student, Louise-Catherine Breslau.

Maria's works were praised by recognized artists – all to her schoolmates' unconcealed envy. There is one more enviable achievement on her record: the seven-year course at Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which she completed in just two years.

A lesson at Julien's School. Oils, 1879

In January 1879, Maria won an academic competition and received a gold medal – her first award. A year later, her painting Young Woman Reading was presented at the Salon, the official art exhibition of Académie des Beaux-Arts. It was a moment of glory that many artists could only dream of.

At that time, Salon exhibitions were widely covered in the press and the mention of the young debutante meant a huge step – even leap – to recognition while works that were not exhibited at the Salon hardly had a chance to sell.

Young Woman Reading. Oils, 1879

Praised by art critics and courted by nobles, Maria continued to work hard, improving her techniques and diversifying genres, while her state of health deteriorated. She lost her hearing and almost constantly suffered severe pain. Medical treatment was of little help and – as she was all too aware of the inevitable – she tried to make the most of each remaining day.

Self-portrait. 1880

Maria presented three canvases to the Salon and each received the expert jury's high appraisal. Her name appeared in the French and international press and was also heard of in her homeland. She did attain her goal of becoming famous, but she was not happy, being aware of her incurable disease, and had to force herself to remain a beau monde beauty in all respects.

Maria Bashkirtseva. Paris, 1881

In 1882, she joined the suffrage movement and published articles in the Paris magazine La Citoyenne under the pen name Pauline Orei. She slammed and ridiculed the double moral standards of contemporary French society where female artists were barred from exhibiting their works on an equal footing with men.

She maintained that, by denying women equal access to art education and opportunities to compete on equal terms with men, the latter sought "to prevent [women] from exposing the same men's incapability."

An indignant response from Guy de Maupassant to Maria’s witty and biting remarks started their long and interesting correspondence. A celebrated writer, beau monde lion and Paris playboy who took ladies' hearts easily and quickly, de Maupassant was confused by the intellect and style of someone who wrote to him in such a gritty manner. He assumed with irritation that he was corresponding with an old nerdish teacher rather than a young Ukrainian woman.

The renowned French artist Jules Bastien-Lepage visited Maria’s studio and was fascinated with her works. Inspired by his praise, Maria started working on her painting Holy Women, depicting the Virgin Mary and Maria Magdalena sitting by the cave where Joseph of Arimathea buried Jesus Christ.

Holy Women – unfinished.

Unfortunately, the painting remained unfinished. Maria Bashkirtseva, who still had so much to tell and show to the world, succumbed to tuberculosis on Oct. 31, 1884.

Hearing the news of her death, Guy de Maupassant exclaimed in despair, “She was the only Rose in my life. I would have paved her path with flowers, had I known that it would be so bright and so short!”

Maria was buried in Paris. Her easel, palette and unfinished Holy Women were placed inside the mausoleum that was built at the site of her grave.

Mausoleum at Cimetière de Passy in Paris, the burial place of Maria Bashkirtseva, along with some of her relatives.

Legacy

A year after Maria’s death, a major personal exhibition of her works was held in Paris. A street in Nice was named after her, and her canvasses are still on permanent display at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice.

At Palais du Luxembourg in Paris, Maria Bashkirtseva's name is engraved at the foot of the symbolic sculpture Immortalité alongside the names of great French figures.

All-in-all, she left behind around 150 paintings. Several remained in the Louvre and a few more were bought by museums. Her mother brought almost all of them, as well as other works, to the family estate in Havrontsi and later handed 141 paintings, drawings, sketches and sculptural etudes over to the Alexander III Museum in St. Petersburg.

The larger part of the collection was lost with the windstorm of the 1917 Bolshevik coup and many other works perished in World War II.

The few paintings that survived are now kept in French, Dutsch, US and Russian museums, and only three of them can be found in Ukraine – in Kharkiv, Dnipro and Sumy.

The original Diary – not the one published in 1887 and translated into several languages – was accidentally found in the 1980s in the Russian National Library.

Expert studies discovered that the original text had since been substantially “edited” by Maria’s mother: there were numerous “gaps” and fact distortions (including the actual year of Maria’s birth) in the published version. Experts assumed that her mother must have made these changes to conceal certain family secrets.

The complete Diary (part one: I Am the Most Interesting Book of All, part two: Lust for Glory), which was translated into English in 2012, reveals the amazingly rich inner world of the woman who described surroundings, events, emotions and thoughts so vividly and frankly.

Very regrettably, neither version has been translated into Ukrainian, although there is every reason for Ukraine to be proud of her extraordinarily gifted daughter.

Last photograph of Maria Bashkirtseva. Paris, 1884

To this day, dozens of prominent Ukrainian names have been appropriated by Russia where all schoolbooks, encyclopedias and search engines mention them as "Russian". These include Mykola Hohol, the great Ukrainian writer; Illia Repin and Kazimir Malevich, the great Ukrainian painters; Oleksandr Vertynsky, the great Ukrainian singer and actor; Ivan Piddubny, the great Ukrainian strongman; Vera Kholodna, the great Ukrainian silent movie star; Serhiy Korolyov, the great Ukrainian spacecraft designer – and many more.

This is, unfortunately, also true for Maria Bashkirtseva, one of the great Ukrainians whose name and fame were stolen by Russia.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter