This year marks the 82nd anniversary of the Babyn Yar tragedy and another mournful anniversary: the crimes committed by the Nazis in Babyn Yar became known in early November 1943, shortly after Kyiv was liberated from the Nazi occupiers by Soviet forces.

On Sept. 29, 1941, Babyn Yar, the historical ravine on the then northwestern outskirts of Kyiv, turned into a place of massacre, which continued there throughout the entire period of the Nazi occupation of the city. During that period, more than 100,000 people were killed in Babyn Yar. In the first weeks of mass executions, most of the victims were Jewish women, children and elderly people.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

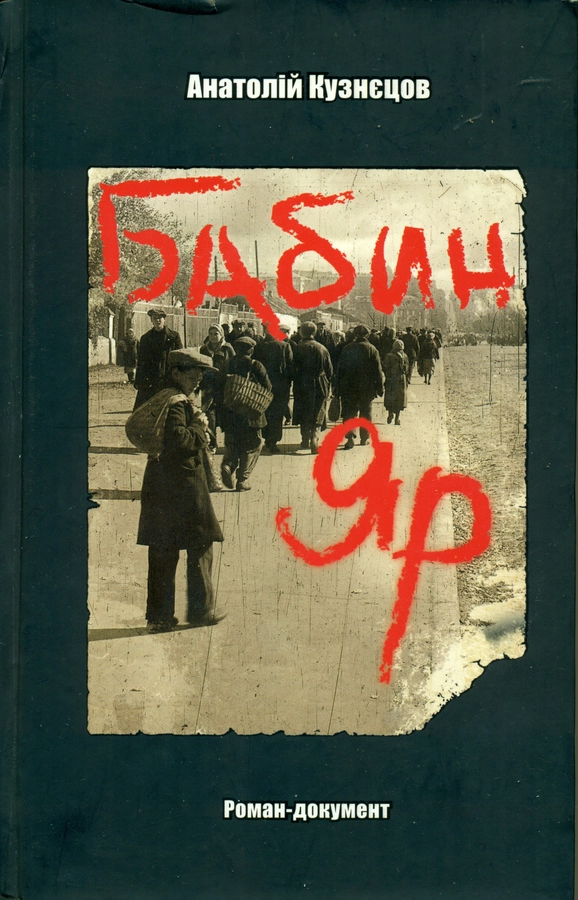

Honoring the memory of the dead, we must also remember our countryman born in Kyiv, writer Anatoly Kuznetsov (1929-1979). He is the author of the novel Babi Yar (Babyn Yar in Ukrainian), who was the first to tell the world about this tragedy.

Twelve-year-old Kuznetsov survived the occupation of Kyiv. He lived near Babyn Yar and witnessed those horrible events.

In 1966, Babi Yar came out in three issues of the popular Soviet magazine Yunost, albeit abridged as a separate edition of the novel published the following year.

Despite being censored, the novel was translated into several languages and published in a number of countries. Babi Yar brought its author well-deserved recognition, so the news of the writer’s escape during a business trip to England in late July 1969 hit many as a thunderbolt.

Peace? Not Yet. And Here’s Why

Anatoly Kuznetsov was considered a successful author. He was a member of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union of Writers, as its secretary in Tula, where he lived at the time. It became known almost immediately that Kuznetsov had taken copies of his works with him, including the complete, uncensored text of Babi Yar. The novel was published in the West, and the author asked to consider only this edition of the book to be valid.

Babi Yar immediately became a world bestseller. It was published in more than 50 countries. The book was not only a stunning story about the crimes of Nazism. The writer openly emphasized the similarity of the two totalitarian regimes of Germany and the USSR. The novel also mentioned the 1932-33Holodomor in Ukraine , as well as the Kurenivka tragedy in Kyiv, when the dam broke on March 13, 1961 after the Soviet authorities had turned part of Babyn Yar into a construction site. Thousands of citizens died because of this disaster.

Kuznetsov used three different fonts in the new edition of Babi Yar. One was used for the text as in the Yunost edition, another font marked the parts of the text removed by Soviet censorship, and the third showed what the writer added when he lived in Tula in 1967-69 and realized that it would not be possible to republish the book. Thus, the new edition of the novel became a testimony to the “work” of Soviet censorship.

The writer is remembered and revered in the motherland: a monument to him was erected in Kyiv, one of the streets in the capital is named after him, and the novel Babi Yar was published in Ukrainian and included in the school curriculum. However, probably not all admirers of his work know that he tried his hand at filmmaking as well.

Kuznetsov and films

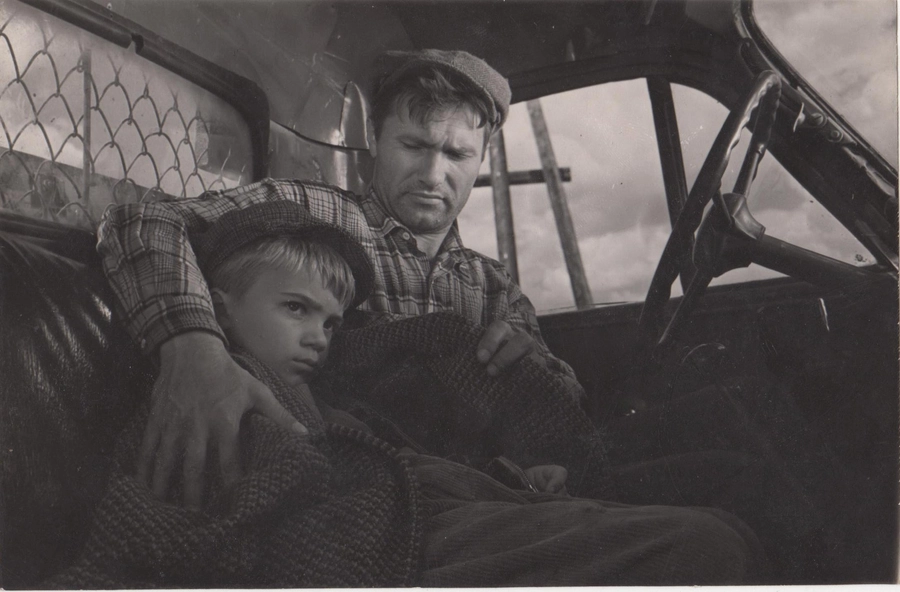

In 1962, filmmaker Yuriy Lysenko shot the film We, Two Men at the Dovzhenko Film Studio according to the scenario of Anatoly Kuznetsov. The author wrote the script based on his story Yurko-a Little Fellow. Kuznetsov said it was a simple story about a drunk driver who becomes humane and begins to take care of a little boy.

However, the process of bringing such a seemingly simple story to screen turned out to be complicated and full of vicissitudes. First, filmmaker Mechyslava Mayevska, already known for the films A Pedagogical Poem (1956) and A Partisan Spark (1958) shot together with Oleksiy Masliukov, was involved in the work on the future film. However, there was no success. Then Sergei Parajanov was brought in to work on the movie, but in the end the work was entrusted to another filmmaker – Yuriy Lysenko.

Filming began, but soon it became clear that it was necessary to replace the lead actor, since the film studio management and the filmmaker himself were dissatisfied with him. Instead, they invited another actor – Vasyl Shukshin – young, but already known for his roles in several films, especially in Two Fedirs (1959), which was shot at the Odesa Film Studio by filmmaker Marlen Khutsiyev.

After replacing the actor, additional difficulties arose. Time was running out, part of the budget had been spent, they managed to shoot a number of episodes in Kaniv and Kyiv, but the weather deteriorated, therefore the film crew was forced to go to Crimea.

At first, the picture was called The Road Goes Nearby, and later it was renamed We, Two Men. The management was not satisfied with the finished film, criticized the picture and forced the team to redo it. Undoubtedly, they were alarmed, as no mention of the leading role of the party had been made, and the main character did not fit the image of a person building a bright socialist future.

By coincidence, it was at this time that the well-known film critic and editor-in-chief of the Art of Cinema magazine Liudmila Pogozheva came to the film studio from Moscow on business. She watched We, Two Men and liked it. Pogozheva returned to Moscow and wrote a favorable review, which was printed in the main Soviet newspaper Pravda. The film studio directorate saw this as a sign, and the film was accepted.

Then the film was unexpectedly included in the competition program of the Moscow International Film Festival in 1963. Yuriy Lysenko and Anatoly Kuznetsov were invited to personally present their film. Soviet cinematography in the program of the festival was to be represented by We, Two Men of the Dovzhenko Film Studio and Meet Baluyev produced by the Russian film studio Lenfilm.

Already in London, in one of his programs on Radio Liberty, Anatoly Kuznetsov recounted what happened next. The members of the international jury of the film festival, including the popular French actor Jean Marais and the American film director Stanley Kramer, did not like Meet Baluyev. We, Two Men was supposed to be shown two days later, but that did not happen.

Suddenly, it was decided to withdraw We, Two Men from the program of the festival, without notifying Lysenko and Kuznetsov and without explaining the reason. Kuznetsov suggested that after the failure of the first Soviet film, the management probably decided to once again watch their film and concluded that the joy of socialist construction was missing in the picture, and the life of the provinces was not properly presented. Serhiy Lysetsky, director of the film, recalled that they filmed under the influence of Italian neorealism movies popular at the time and tried to reproduce reality on screen as realistically as possible.

At the request of the festival organizers, the program was changed. They showed An Empty Flight produced by Lenfilm instead of We, Two Men. At the closing ceremony, this film ranked third, as it would be inappropriate not to award the host country.

Ordinary viewers and guests of the film forum had no idea what was happening around the Grand Prix behind the scenes. After a long and intense debate, Federico Fellini’s movie 8 ½ – now recognized as a masterpiece of world cinema – received the award.

The box-office receipts of We, Two Men in the Soviet Union were quite modest, but this controversial experience did not deter Kuznetsov from further attempts to write scripts. He seemed to have been pleased with his cinematic debut, as he recalled: “A miracle happened, the camera captured life.” Indeed, this film still makes an impression with its sincere tone conveying the spirit of the so-called Khrushchev Thaw period (when repression and censorship were relaxed).

Kuznetsov returned to work in cinema a few years later, in the late 1960s, after Babi Yar had been published.

The Mosfilm film studio approved and put into production Kuznetsov’s script based on his novel At Home.

At the same time, the writer submitted an application to the Dovzhenko Film Studio for the script A Man and the Night based on his novel Babi Yar. The book was a success, so the film studio leadership approved the application and concluded an agreement to write the script. Then the artistic council considered the first version of the script, accepted it, but with numerous suggestions and the requirement to finalize it. Filmmaker Artur Voitetsky was to shoot the film.

However, the work on the second version of the script was delayed. At the request of the author, the deadline was postponed several times.

The premiere of the film Meetings at Dawn, directed by Eduard Gavrilov and Valeriy Kremnev according to Kuznetsov’s script based on his novel At Home took place in Moscow on June 16, 1969.

The defection

On July 30, 1969, the writer went on a business trip to London to collect material for the upcoming book dedicated to the centenary of the birth of Soviet politician Vladimir Lenin. After four days, he requested political asylum, and the British government granted his request.

The decision not to return was not spontaneous. In one of his radio programs, the writer told how long he had been preparing to escape and even planned different options for crossing the border.

In addition, changes in the USSR foreign policy pushed him to break away from the country. In 1967, the Six-Day War took place in the Middle East, in which Israel defeated the joint forces of Syria and Egypt. The Soviet Union supported the Arab countries in the war. The USSR broke off diplomatic relations with Israel. Periodicals began to publish articles about “aggressors” and “Zionists.” Any topic related to the extermination of Jews during the Second World War became uncomfortable and undesirable.

Kuznetsov realized that it was futile to hope to publish Babi Yar in its entirety, and that making a film based on the novel would be difficult. According to him, the last straw was the events of Aug. 21, 1968, when Soviet troops together with units of the Warsaw Pact countries occupied Czechoslovakia.

In the end, the fact that he prepared photocopies of all his works, including the original text of Babi Yar, which he considered the main work of his life and was supposed to tell the world the truth without censorship, testifies to the writer’s conscious decision.

The reaction of the Soviet authorities to the famous writer’s failure to return did not take long: We, Two Men and Meetings at Dawn were withdrawn from exhibition. Moreover, by order of the Ukrainian SSR State Committee for Cinematography, work on A Man and the Night was stopped. All of Anatoly Kuznetsov’s works, as well as both editions of Babi Yar, including the book published in 1967 and three issues of the magazine Yunost dated 1966, were removed from bookstores and libraries.

In 1985, the period of perestroika (restructuring) began in the USSR. Films that were earlier banned began to be “taken off the shelves.” We, Two Men and Meetings at Dawn returned to audiences. Finally, the full version of Babi Yar was released.

It’s been said that Anatoly Kuznetsov remained the author of only one work, because he did not write anything new in exile. Far from it: he recorded a large number of author’s programs on Radio Liberty in London. The writer’s son Oleksiy Kuznetsov compiled and published the book Anatoly Kuznetsov at Liberty based on these radio programs, rightly believing that in this way his father was continuing the format of “confessional prose” he had begun as a writer in journalism.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article stated Kuznetsov's died in the year 1969. It was in fact 1979.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter