Ukraine as a Mirror of the Wonder and Potential of Our Planet

When I awoke, the sun was obscured by a thin film of milky fog. I could stare directly at it, until, when the fog evaporated by late morning, the glare forced my glance downwards towards the spectacle at which, from the train window, I stared in wonder for the next three hours.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Rushing past me, the stunning beauty of Ukrainian forests in autumn. And believe me reader, words are inadequate. You must see it for yourself. The sunlight caught the canopies of the beech, the alder, the poplar, transforming them into an efflorescence of gold, flashes of red autumnal maple and cherry and the russets and browns of chestnuts and willows. The colorful cyclical ceaseless changes of life as the Earth, insensible to human ambitions, fulfils its own mysterious journey.

A Remarkable Scientific Conference in Kyiv

And this connection between life and its environment was behind the purpose of my journey to Kyiv. It was to co-chair Ukraine’s first international planetary sciences and astrobiology conference, pulled together with friends and colleagues from a number of institutes and hosted by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU). The title of the meeting, held from Oct. 23 to 26, was “Planetary research and the search for life beyond Earth.”

The scientific field of astrobiology tackles questions that resonate deeply with all of us: How did life begin? How did we get from the first single cell that existed billions of years ago to a creature sitting in a train wistfully watching the Ukrainian forests? To complex creatures talking about science in the Ukrainian capital? Will we ourselves one day explore and settle space? And perhaps its most thrilling question: Could there be life elsewhere, or is Earth the only instance for all these strange and oddball creatures we call life?

All these questions sit at the boundary of astronomy (the science of stars, planets and much else ‘out there’ in space) and biology, the science of life. Hence, the field of astrobiology.

Our conference brought together the Main Astronomical Observatory (MAO) (the ‘astro’ part of our meeting) and the Institute for Molecular Biology and Genetics (IMBG) (the biology part of the meeting), both institutes of NASU. Also involved was the Space Research Council of NASU and the Ukrainian Astronomical Association, both of whom have an interest in furthering the development of space science in Ukraine.

This was a truly international meeting, and although many of us gathered in Kyiv to share ideas and talk about science, speakers joined us remotely from Germany, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, Italy, Spain, Austria, China, Hungary, and from my own research home, the UK Centre for Astrobiology in the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh (also a co-host of the conference). Over 26 speakers presented their ideas. In the true spirit of an attempt to physically bring together the astronomers and the biologists, we held two days of our four-day meeting in the MAO and two days in the IMBG.

Astrobiology – the global and Ukrainian dimensions

In recent years, astrobiology has advanced enormously, partly because of the increasing number of robots we send to distant planets like Mars and the icy moons of the outer solar system that are known to contain oceans. These are places that we think may host conditions suitable for life. New missions are making it possible to explore them to discover if they ever hosted life, and if not, why not.

Soon there will be new telescopes that will seek life on planets orbiting stars far away from our own Solar System, so-called ‘exoplanets’.

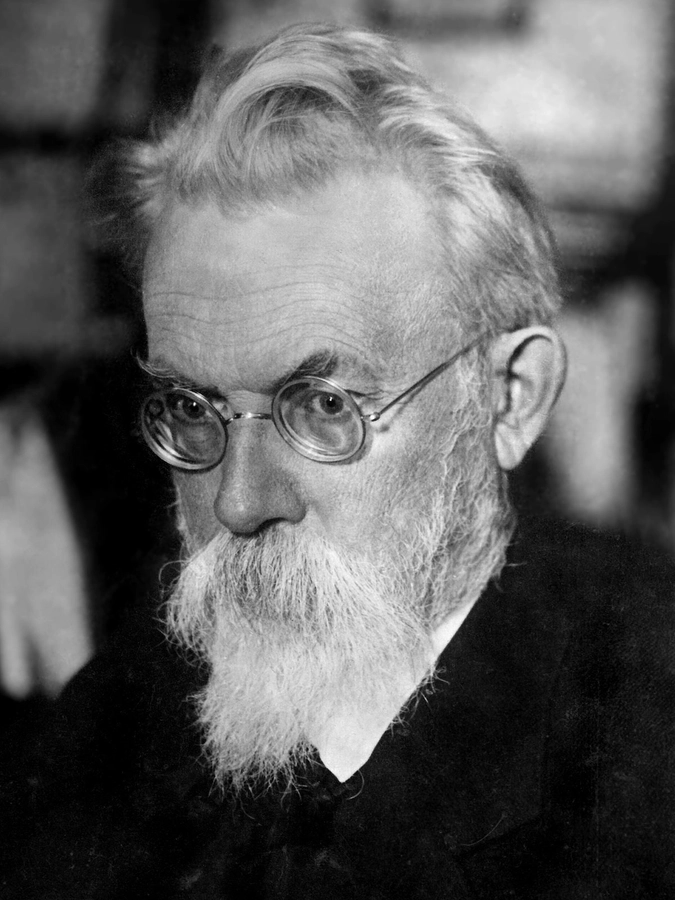

But do not be under the illusion that astrobiology is a new science. Astrobiology may be a relatively new name, but eminent scientist Volodymyr Vernadsky (1863-1945), who in 1918 became the first President of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, was an early twentieth century pioneer of the science who wondered about how life takes over the planet it inhabits and changes its development.

Volodymyr Vernadsky. Photo: Wikipedia.

Vernadsky’s famous 1926 book, The Biosphere, popularized a term with which we are now all familiar. His treatise contemplated life on the big scale, how it becomes an enormous biological machine integrated into the geology of a whole planet. In many ways, he was an early astrobiologist.

In Kyiv, we were thrilled by talks that informed us about how to look for life on distant exoplanets; how to study comets, asteroids, and other planetary bodies; how to seek signs of life in ancient rocks from early Earth and on Mars; and much more. What we witnessed was the high regard with which the international community holds Ukrainian science, and the enthusiasm for the Ukrainian contribution in this field, especially among young scientists.

Already Science4Kids, a Ukrainian initiative, is taking the excitement of space and biology to a new generation of Ukrainians as part of an effort to carry the wider importance and excitement of science into schools and out to the public.

Why this Conference Now?

Despite all this interest, it is quite reasonable for someone to ask: Is it really a priority to organize conferences about planetary exploration during wartime. Surely, we have more important things to do right now?

In response to this eminently sensible question, I think there are at least two answers.

First, many of us believe in a civilization where people are at peace and have time to contemplate great scientific questions and advance our understanding of humanity’s place in the universe. We fight for a civilization where these sorts of questions attract our fascination, and our time.

To turn this on its head, one could say that it is particularly during war that we should commit ourselves to continuing to advance science as a demonstration of the type of society we want. War intensifies our determination to continue these activities, not lessen them. The same argument applies to why we should doggedly continue doing great art and writing extraordinary literature when war threatens to destroy them.

A second point is a more political one. It is true that scientists try to keep politics out of science. The universe cares not one iota about human affairs. Thus, in trying to unravel the mysteries of the universe, we must keep this work isolated from our political opinions. Yet, it’s true to say that a healthy scientific culture is one in which people can question existing ideas, challenge authority, and have the freedom to express these thoughts without interference or the threat of intimidation. These are the same values that more generally underpin societies of free-thinking human beings. It's inescapable that a good scientific culture is part and parcel of a wider political culture of freedom.

Science and Freedom

It's perhaps no coincidence that the rise of science beginning in the seventeenth century was contemporaneous with the emergence and spread of liberal democratic societies. It generally seems to be the case that a free political environment is one in which scientific enquiry can most successfully thrive, and conversely, the attitudes and approaches of science are a healthy encouragement to open political societies. Science and politics are conjoined in the ideas of liberty.

As another example, one might contemplate the remarkable explosion of philosophical schools and early scientific ideas in ancient Athens two millennia ago compared to its less creative neighbor, Sparta. It seems to be no coincidence that the former was a democracy reared under ideas of liberty and the latter a more rigid military autocratic state.

When we are at war, this is not a time to stop science and call into question scientific meetings, but rather to reaffirm the ideas of open societies and to persist in bringing scientists together internationally to display an example of the intellectual environment we strive for. We want to build a scientific civilization, and this requires a society committed to the pursuit of unrestricted discussion, honest and truthful discourse, and peace.

Conclusions

This was an excellent time to gather in Kyiv. Ukraine has recently launched miniature satellites into orbit and the institutes of NASU have been involved in biological experiments onboard the International Space Station. Even without the war, it would still be timely to unite different scientific fields to affirm the Ukrainian contribution to a growing and exciting field of science.

However, it is undoubtedly true to say that the war makes it especially impressive that Ukrainian scientists were able to coordinate and make four days of energized discussion possible, and so successful, at relatively short notice.

One hopes that this meeting is one of many scientific and educational initiatives that will bring different scientists together in Ukraine and around the world to answer some of the most compelling questions about the universe.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

Charles Cockell is Professor of Astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter