U. S. President Donald Trump faces impeachment over his alleged pressure on Ukrainian officials. But his administration is hardly the first example of unorthodox ties between the United States and Ukraine.

In 2017, the administration of then-President Petro Poroshenko covertly hired American lobbyists to help boost Ukraine’s profile in Washington. It paid $600,000 through a nongovernmental organization that received millions of dollars from Western donors.

- Find the latest Ukraine news published as of today.

- View the most up-to-date Ukraine news articles published today.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The lobbying group, BGR, may have even helped Ukraine to get what it desperately wanted and what the U.S. had been declining to provide for years — lethal weapons to help it defend itself against Russia’s war, specifically Javelin anti-tank missiles.

Tying this story to the current impeachment scandal is Kurt Volker, Trump’s former special envoy to Ukraine who helped him put pressure on Ukraine’s leaders to dig up dirt on the U.S. president’s rivals. Volker also works for the same lobbying firm that Poroshenko hired.

BGR employee Volker appeared to strongly support selling Javelins to Ukraine, according to Politico. Moreover, BGR is also a lobbyist for a firm that manufactures Javelins and profited from the sale to Ukraine.

Volker now faces allegations of attempting to broker a quid pro quo trading military aid from the U.S. for a “favor” from Ukraine — an investigation into former U. S. Vice President Joe Biden, Trump’s possible rival in the 2020 presidential elections.

The council

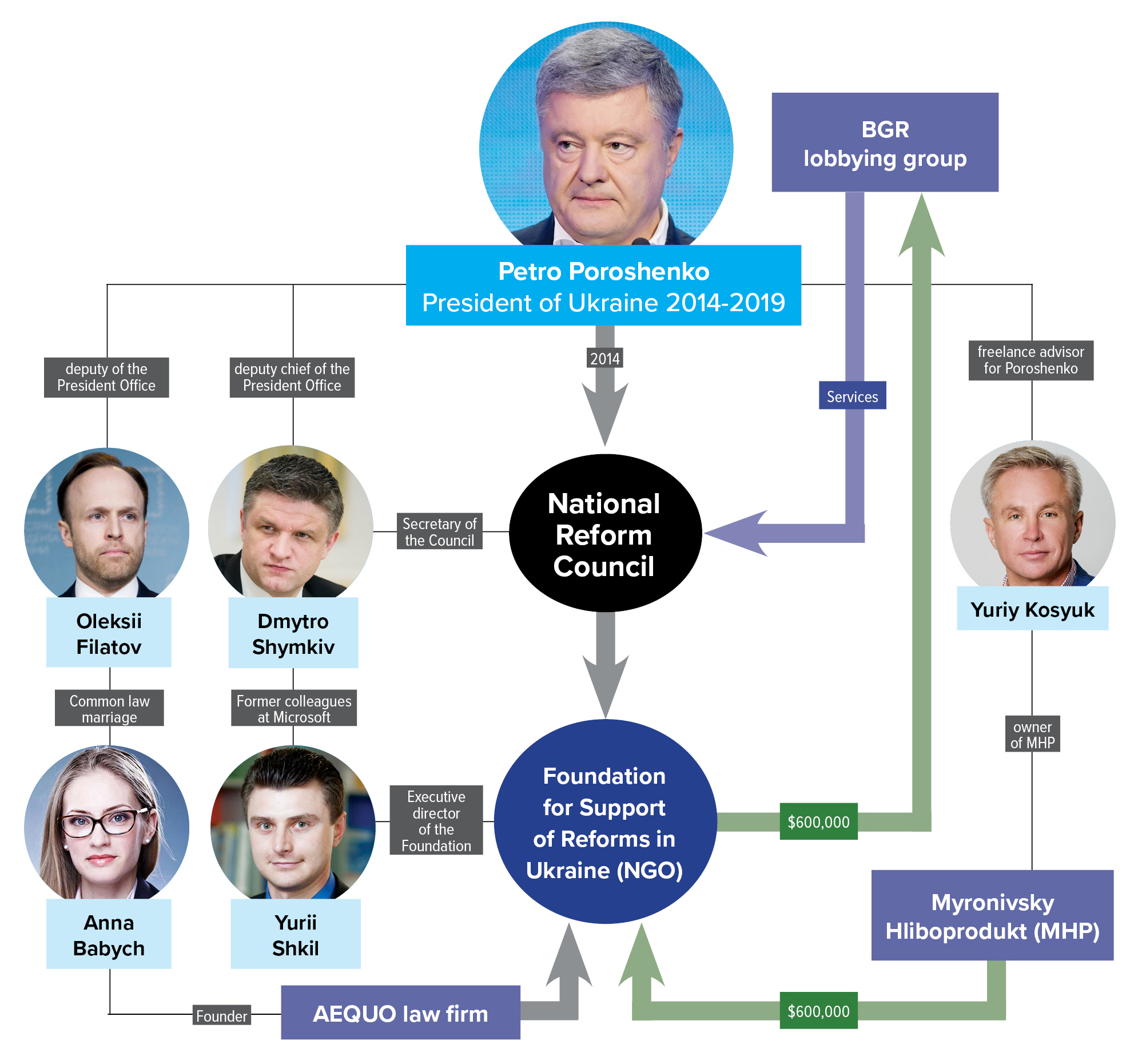

In 2014, Poroshenko created and chaired the National Reforms Council, designed to seek political consensus among governing bodies when planning and implementing reforms. The council’s legislation says the organization must be “transparent and public.” It failed at that.

Instead, the National Reforms Council swept some of its most interesting activities under the rug, including the hiring of BGR.

Poroshenko staffed the council with his allies in parliament and the Cabinet of Ministers. They would meet once or twice a month. According to the presidential office website, their last session was on March 2, 2018, a year before Poroshenko lost re-election and stepped down from the presidency.

The council has few achievements. It’s not clear what exactly it was doing. All of its reports were vague in wording.

But its associated non-governmental organization, the Foundation for Support of Reforms in Ukraine, is more interesting.

Since its creation in 2015, the NGO has absorbed millions of dollars from Western donors like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Transparency International, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the British Embassy. Among its largest sponsors is the Western NIS Enterprise Fund, funded by the U.S. government. The NGO also accepted money from Ukrainian businesses.

The NGO spent its donors’ money on, for example, an international mayors’ summit in 2018, developing tourism initiatives, and among other things, BGR lobbying.

Ties to Poroshenko

While the NGO claims absolute independence from the state on its website, there are a few strong connections.

The NGO was established by AEQUO, a law firm co-founded by Anna Babych, the common-law wife of Oleksii Filatov, who served as Poroshenko’s deputy head of administration from 2014 to 2019.

When Filatov joined the presidential office, Babych launched AEQUO and obtained a number of lucrative contracts with state companies. Filatov was widely criticized for allegedly helping Babych, and in June 2018 the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine launched an investigation into possible illicit enrichment by Filatov. It was then passed to the police.

The NGO’s executive director, Yurii Shkil, is also linked to the Poroshenko administration and the National Reforms Council. Dmytro Shymkiv, then-secretary of the council and another deputy chief of the presidential administration, had worked closely with Shkil at Microsoft Ukraine for years.

BGR lobbying

BGR lobbying

In January 2017, the Foundation for the Support of Reforms in Ukraine signed a contract with BGR in which it agreed to fund lobbying on behalf of the National Reforms Council using “private donor funds.”

In a services agreement, the parties emphasized that the council was ordering the lobbying and the NGO was just paying for it.

Under the agreement, BGR would “provide strategic government affairs and public relations assistance” along with “communications with relevant U.S. government officials” and anyone else “interested in the reforms happening in Ukraine.”

During a year and a half of work, BGR contacted more than 150 people to talk about Ukraine. The lobbyists reportedly sent emails, made calls and met with U.S. officials and the media in person, according to Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) reports BGR filed to the U. S. Department of Justice in 2017 and 2018.

There are a few reasons to believe that BGR was working hard to bring Javelins missiles to Ukraine.

The person BGR approached most frequently, Tyler Brace, was a legislative assistant for Republican Senator Rob Portman at the time. Portman is a co-founder and co-chairman of the Senate Ukraine Caucus and was a backer of selling Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, a deal the administration of U. S. President Donald Trump approved in December 2017 in a move Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, declined to make.

Portman even introduced a legislative amendment to boost security assistance for Ukraine in the Senate. It was signed into law in December 2017.

“Now, the United States Senate is taking a critical step forward in its support for Ukraine,” Portman said in a statement. His assistant, Brace, did not respond to the Kyiv Post’s request for comment.

One of the sale’s biggest supporters was Volker. Trump’s special envoy simultaneously worked for BGR and for the McCain Institute think tank. Both organizations have financial ties to Raytheon Co., a company that produces Javelins and earned millions from the decision to provide Kyiv with the weapons.

According to the OpenSecrets organization, the Javelin manufacturer also paid BGR $1.6 million for lobbying services over the past 10 years.

Volker resigned from his special envoy post on Sept. 27 after news broke that he was among the officials involved in efforts to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate the son of Joe Biden.

Volker and Poroshenko

Having pressured Ukraine to investigate Biden, Volker also asked current top officials in Ukraine not to prosecute Poroshenko.

That emerged from a transcript of U. S. chargé d’affaires in Ukraine Bill Taylor’s testimony in the ongoing impeachment probe, which was released on Nov. 6. “Ambassador Volker suggested…that it would be a good idea not to investigate Poroshenko,” Taylor said.

The former Ukrainian president currently faces 11 charges involving possible abuse of power.

Contacted by the Kyiv Post, BGR strongly denied that Volker was assigned to work for the Poroshenko-chaired council.

“At BGR, Ambassador Volker recused himself on matters related to the government of Ukraine when he was special envoy,” a BGR spokesperson, Jeffrey H. Birnbaum, told the Kyiv Post.

BGR refused to reveal details about its work for Ukraine. “BGR does not discuss its clients,” Birnbaum said in an email.

In January 2017, weeks before the lobbying contract with BGR was signed, Poroshenko met top BGR executives in Kyiv, Politico reported, citing anonymous sources in Washington and Kyiv.

The BBC later accused Poroshenko of paying $400,000 for a June 2017 meeting with Trump. Poroshenko sued the BBC for libel and won, and the media outlet apologized, agreeing to pay damages.

Cover-up

Poroshenko’s relationship with BGR has never been brought to the light. More than that, it was being carefully hidden by Poroshenko aides.

For two years, both the NGO and the council reportedly denied they had a contract with BGR when they were officially summoned to respond to questions about the relationship by then-lawmaker and current Kyiv Post columnist Sergii Leshchenko.

However, over a year and a half, starting in 2017, FARA reports indicate that the National Reforms Council systematically paid BGR.

BGR, which according to its website helps “international clients navigate Washington,” billed Ukraine for $600,000.

However, these expenses are not reflected in the council’s reports. They are also absent in the NGO’s filings.

Since its creation, the council has published only two annual reports, for 2015 and 2016.

The Kyiv Post brought these findings to Poroshenko’s press office and asked why he hid the hiring of BGR, but did not receive any response.

While the NGO is not obliged to publish its reports under Ukrainian law, it also continuously claimed to be transparent. It did make some of its activity public, but there was no mention of BGR.

Both the NGO’s financial and annual reports for 2017 do not include information on any arrangements with Washington lobbyists; however, the filings for 2018 do reference the U.S.

The annual report says that the foundation was engaged in “promoting Ukraine in the U.S.” in a project that lasted from January to December 2017.

The foundation did not name BGR and did not mention that the cooperation between the two lasted at least half a year longer than indicated — however obliquely — in the filings.

The project was dedicated to “combating disinformation about Ukraine in the U.S.” and “boosting the relationship between Ukraine and the U.S. in cybersecurity,” the annual report says.

The financial report for 2018 says that the foundation spent $600,000 on the “promotion of Ukraine” without providing further details.

Responding to the Kyiv Post’s official information request, the foundation admitted that “promotion of Ukraine” in its 2018 report refers to BGR lobbying in the U. S. At the request of the Kyiv Post, the foundation also disclosed a list of sponsors who funded the lobbying.

It claimed no Western donors but named five Ukrainian agricultural companies.

The firms that gave $600,000 are PRJSC Zernoprodukt MHP, Vinnytska Ptakhofabryka LLC, PRJSC Myronivska Ptakhofabryka, Urozhay LLC and Urozhayna Krayina LLC.

All five are owned by Yuriy Kosyuk, one of the richest people in Ukraine, and formerly an advisor to Poroshenko.

BGR ignored the Kyiv Post’s question on whether it was aware that the National Reforms Council paid for its services with Kosyuk’s money.

MHP’s press office said that the company and its owner Kosyuk did not know their money was paid to BGR. They said that the company donated to the NGO to help the development and implementation of reforms in Ukraine.

Who is Kosyuk?

Yuriy Kosyuk, often labeled in the local media as “Ukraine’s chicken king,” is the main owner of Myronivsky Hliboprodukt, or MHP, the largest poultry producer in Ukraine. Forbes estimates his fortune at $1.2 billion. Kosyuk is the seventh richest man in Ukraine, according to the most recent ranking by Focus magazine.

Poroshenko appointed Kosyuk as his deputy to manage security services and the military during the peak of the war in Donbas in 2014. Agribusiness owner Kosyuk did not have any experience in defense affairs apart from serving in the Ukrainian army in the early 1990s, which was compulsory.

The businessman handled military issues on behalf of Poroshenko for half a year before resigning in December 2014 to become a freelance advisor for Poroshenko, a position he kept until 2019.

In 2017, Kosyuk launched a startup accelerator with Poroshenko’s daughter-in-law Yuliya.

Despite being owned by a billionaire, Kosyuk’s businesses have long received state subsidies that were designed to help struggling small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises.

In 2017, MHP received $53 million in subsidies, 30% of the entire amount of state support for agriculture.

In 2017, Kosyuk holding’s net profit was estimated at $230 million, three times as much as the $69 million it earned the previous year, according to MHP’s annual report.

The company exports chicken meat to the European Union, the Middle East, and North Africa, which together make up a little more than half of its revenue.

In autumn 2018, Kosyuk received another large subsidy from the state, which covered 23% of the cost of a factory he is building. It is expected to become the largest chicken-processing factory in the world.

President Volodymyr Zelensky recently asked law enforcement to launch an investigation and audit the subsidies Kosyuk received.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter