He was a highly original singer and poet, and mesmerizing actor. Regarded as one of Russia’s best known cultural icons, he captivated audiences from Moscow to Paris, and from New York and Hollywood to Shanghai. The darling of the post-revolutionary Russian diaspora, this epitome of a “decadent bourgeois” was also an idol in the Soviet Union and his fans included even Stalin. In the West, the “Russian” cosmopolitan was befriended by the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich and the Prince of Wales. He was known to them as Alexander Vertinsky.

But there was a secret that he concealed beneath the various masks he wore as an artist, and one that troubled him until he finally came to terms with it in his final years – that he, Oleksandr Vertynsky, was a Ukrainian obliged by circumstances, as in the case of so many of his compatriots, to act more Russian than the Russians.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Vertynsky was born out of wedlock to a lawyer and his mistress in pre-revolutionary Kyiv and orphaned at an early age. He grew up as an urchin deprived of the comfort and love of a family home, but absorbing Ukrainian culture, restricted as it was in its development by the Russian imperial regime of the tsars, that surrounded him.

Trying to make a new start as an actor and singer in Moscow, and then ending up in exile for almost a quarter of a century, he also suffered immensely from homesickness and nostalgia – what he called the loss of a homeland.

But his home in the true sense, as he later recognized, was certainly not the Soviet Union, where on his eventual return in 1943 he felt increasingly out of place and spiritually oppressed. Nor was it Russia, even though he wrote and sang in Russian, and was depicted as its protégé.

In his final years, after decades of wandering and searching, he proudly acknowledged that he had rediscovered his Ukrainian home. Actors at the Kyiv film studios in 1955 were astonished that the “Russian” legend was so enthusiastic about performing in Ukrainian. Vertynsky reminded them that he was one of them, a Ukrainian who had been born in its capital no less.

Young Oleksandr (Alexander is the Russian form), or Shura as he was commonly known, was born on March 20, 1889, and began his artistic strivings as an actor and writer in a Russified Kyiv. The burgeoning Ukrainian national movement, especially its pioneering theater troupes, had as much of an impact on him as the avant-garde of the city’s vibrant modern urban culture. Shura was aware that on his mother’s side he was related to Ukraine’s genius Mykola Hohol, who found literary fame as the “Russian” writer Nikolai Gogol.

In 1912 Vertynsky left for the bright lights of Russia’s metropolis in search of success and fame. While battling in Moscow with the initial hardships and addiction to cocaine, the ambitious and talented Shura gradually established himself as an actor in silent movies, as well as a cabaret performer and exotic song writer. His most popular role was that of a version of Pierrot that he had invented – a clown with a powdered face, dressed in white and later black, who sang miniature novellas-in-song known as ariettas. His early songs, such as “Your Fingers Smell of Frankincense” (dedicated to the star of Russian silent cinema Vera Kholodna, also a Ukrainian), “Kokaneitka,” and “Tango Magnolia” transformed him into a rising star.

All this was interrupted by the Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian Civil War and the Ukrainian national revolution. Vertynsky was an artist first and foremost and was not politically engaged. But he was not comfortable with the Bolsheviks and their totalitarian ideology. In 1920 he fled abroad with the defeated White Russian forces, whose representatives were receptive to his style.

Long years of exile followed, first in Istanbul, then Romania, Poland, Germany and France. He remained in Paris for nine years as a star of Russian émigré cabarets. His new stage persona was that of a refined gentleman in a routine in which poetry, music, and acting – especially the careful calibration of expression and movement of the hands – were very effectively combined.

Vertinsky continued to record and travel, and one of his best-known hits was “Dorogoi Dlinnoyu,” (Along the Long Road) which he popularized but did not actually write. In 1968 it was recorded with English lyrics as “Those Were the Days” by Mary Hopkin and immediately became an international sensation.

Nevertheless, behind the appearance of success, Vertynsky remained lonely and homesick. A bohemian lifestyle, love affairs and an unsuccessful marriage that he later preferred not to talk about, did not remove the lingering melancholia. While in Warsaw in the early 1920s he first requested the Soviet government to allow him to return but was refused.

He made several tours in the Middle East and in 1934 tried his luck in the United States. Despite successful cabaret appearances in New York and Hollywood, his lack of English proved a major handicap. The following year, he moved on to the large Russian community in Shanghai. Here, his attempt to open a nightclub failed, and with Japan exerting its military might in the region, the prospects were bleak.

In 1943, just after marrying a young Georgian woman, Lidiya Tsirgvava, he was permitted by the Soviet government to relocate to the USSR. This was a huge risk for Vertynsky and his wife. Although he was welcomed by the Russian intelligentsia as reminder of another era and witness of the outside world, he was regarded as essentially a former traitor who remained politically suspect.

The artist was allowed to perform, but even though his concerts were almost always sold out, he was never invited to perform on radio or interviewed or written about in the press. For the next 16 or so remaining years of his life, Vertynsky performed in virtually all the major and smaller cities of the Soviet Union several times over. The state made a fortune from the revenues but he was not in a position to complain too loudly.

In the early 1950s Vertynsky was able to renew his passion for acting in films and his brilliant portrayal as an anti-Soviet cardinal won him the Stalin Prize in 1951. During the filming in Lviv, some of the locals mistook him for a real cardinal and, as he recorded, eagerly began kissing his hand.

But the toll of conforming to Soviet life for this former bon vivant – exacerbated by Khrushchev’s acknowledgement in 1956 of some of the terrible truth about Stalin, his methods and the millions of victims – was immense. Vertynsky wrote to his wife that if it were not for her and their two daughters he would have already committed suicide.

Ultimately, it was Ukraine that gave Vertynsky a new lease on life. He spent more and more time in Kyiv and in 1955-56 played roles in two films in Ukrainian. Given that the promoters of Russia’s imperialistic culture were reluctant to give up the likes of Vertynsky, hardly surprisingly, both Ukrainian versions subsequently “disappeared.” In his home city, the artist brushed up his knowledge of Ukrainian and Ukraine’s history and, as his letters indicate, spent his free time visiting ancient churches and other cultural monuments. His dream was to play the film role of Ivan Mazepa, the Ukrainian leader who in 1709 sided with the Swedes against Peter the Great.

In September 1955, for example, Vertynsky wrote from Kyiv to his wife in the Soviet capital that he wished he could spend the remainder of his life in Kyiv. “What is Moscow for me? I don’t like it,” he confessed. “Ukraine is my native mother…” He added words that today would shock Russians and surprise many Ukrainians. “It’s a shame that I sing only in Russian and am entirely Russian, I should have been a Ukrainian singer and sung in Ukrainian… Sometimes it seems I commit a crime because I don’t sing for her [Ukraine] and in her language.”

Just before his death at the age of 67 in Leningrad in April 1957, Vertynsky wrote a screenplay for a film about a man who had lost and re-found his homeland. He wanted it filmed in Kyiv but the project was never realized. Two weeks before his death, while in Kyiv, he scribbled a poem on a napkin about his love for Kyiv and Ukraine, his spiritual home. Finally, he wrote, his “rebellious youth” had been returned to him. This was the final testament of Ukraine’s prodigal Pierrot.

Five years after his death, a condensed, heavily censored, version of his memoirs was published in a Soviet journal. It omitted his childhood in Ukraine but nevertheless contained hints about his spiritual ties with his native land. In subsequent Russian Soviet and post-Soviet publications about Vertynsky, he was depicted as a quintessential, if problematic, Russian genius. More recently, in 2021 an 8-episode Russian TV biographical drama series portrayed him as “the most famous Russian chansonnier of the twentieth century…The story of the artist who left Russia in 1919 and returned to the USSR in 1943.”

Fortunately, Vertynsky’s widow helped to set the record straight for those fortunate enough to get hold of the collection of their letters which she published in Moscow in 2004 under the title “Siniaia ptitsa lyubvy” (The Blue Bird of Love). From these it is clear who “Shura” really was. She recorded that when she visited him in Kyiv, he proudly took her to see all the main churches and cultural monuments. And his daughter recalled that before going on stage he would prepare his voice by singing Ukrainian songs.

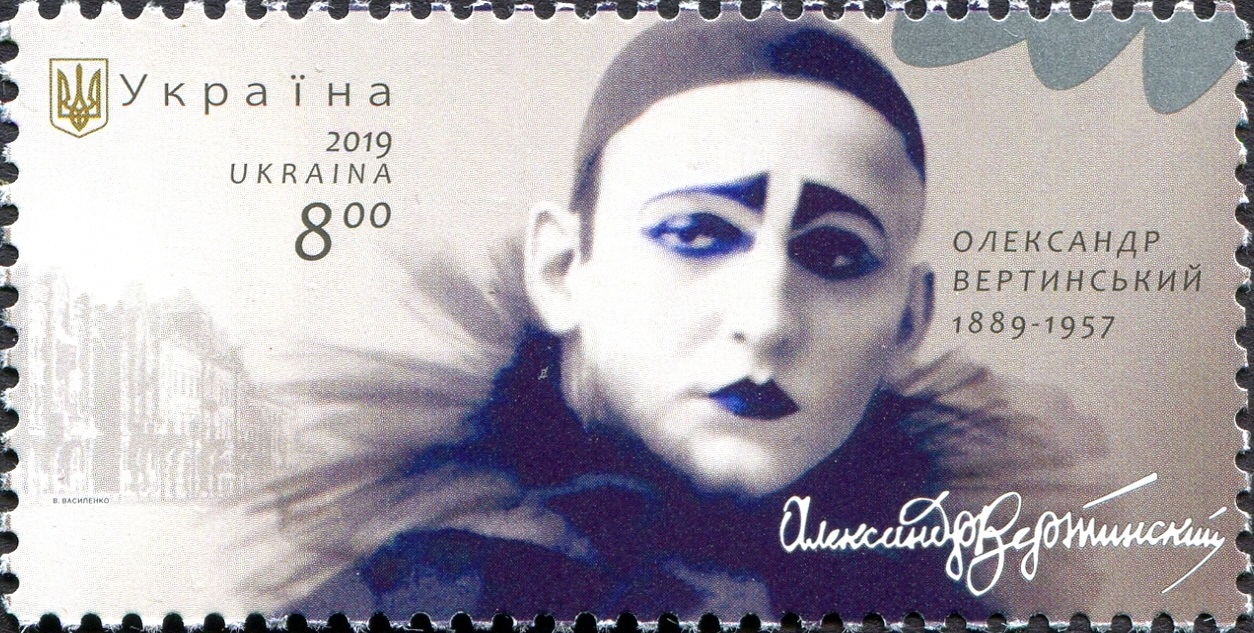

In 2019, on the 120th anniversary of Vertynsky’s birth, Ukraine’s post office issued a special commemorative stamp to honor his memory. Today, as Ukrainians eradicate the vestiges of Russian cultural domination and regimentation, Vertynsky’s wish that he be recognized as a Ukrainian should be honored all the more.

This article is based on an earlier shorter version which appeared in the October 2018 issue of the monthly in-flight magazine of the Ukrainian International Airlines – Panaroma.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter