In this second article on the critical threat to Ukraine from landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW), Kyiv Post examines how the actions of Ukraine and its partners have addressed the need for mine action to date and looks forward to what needs to be done in the future.

Ukraine and the Five Pillars of Mine Action

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) defines those activities which reduce the physical, social, economic and environmental impact of landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) as “mine action” and is much more than the mere removal of unexploded munitions. It also identifies and includes efforts to protect people from danger; help, rehabilitate and care for landmine victims; provide opportunities for stability and sustainable development. This is encapsulated in the so-called “Five Pillars of Mine Action.”

Explosive ordnance risk education (EORE)

Previously called Mine Risk Education (MRE), the term explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) more accurately addresses the risk from both landmines and ERW. EORE provides informational activities to raise the awareness of the ERW threat and, as such, is an indispensable, integral part of mine action. It does not only inform people about what explosive ordnance looks like, but also aims to encourage behavioral change. Like it or not, you can no longer do things the way you used to if you are going to live safely in affected areas and resume meaningful economic and social activity.

Kyiv Reports Surge in Russian Queries on Missing Troops

In response to the 2014 invasion the Ukrainian government, supported by UN agencies, such as UNICEF, and international NGOs – including the HALO Trust, Danish Demining Group (DDG), Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), Handicap International (HI) and the Swiss Demining Foundation (FSD) – carried out extensive EORE in areas close to the disputed areas of the Donbas.

However, after the 2022 Russian invasion, it became much harder to conduct EORE close to the contact lines between opposing forces because of the threat the Russian occupiers posed to the staff involved in EORE activity, who are predominantly Ukrainian.

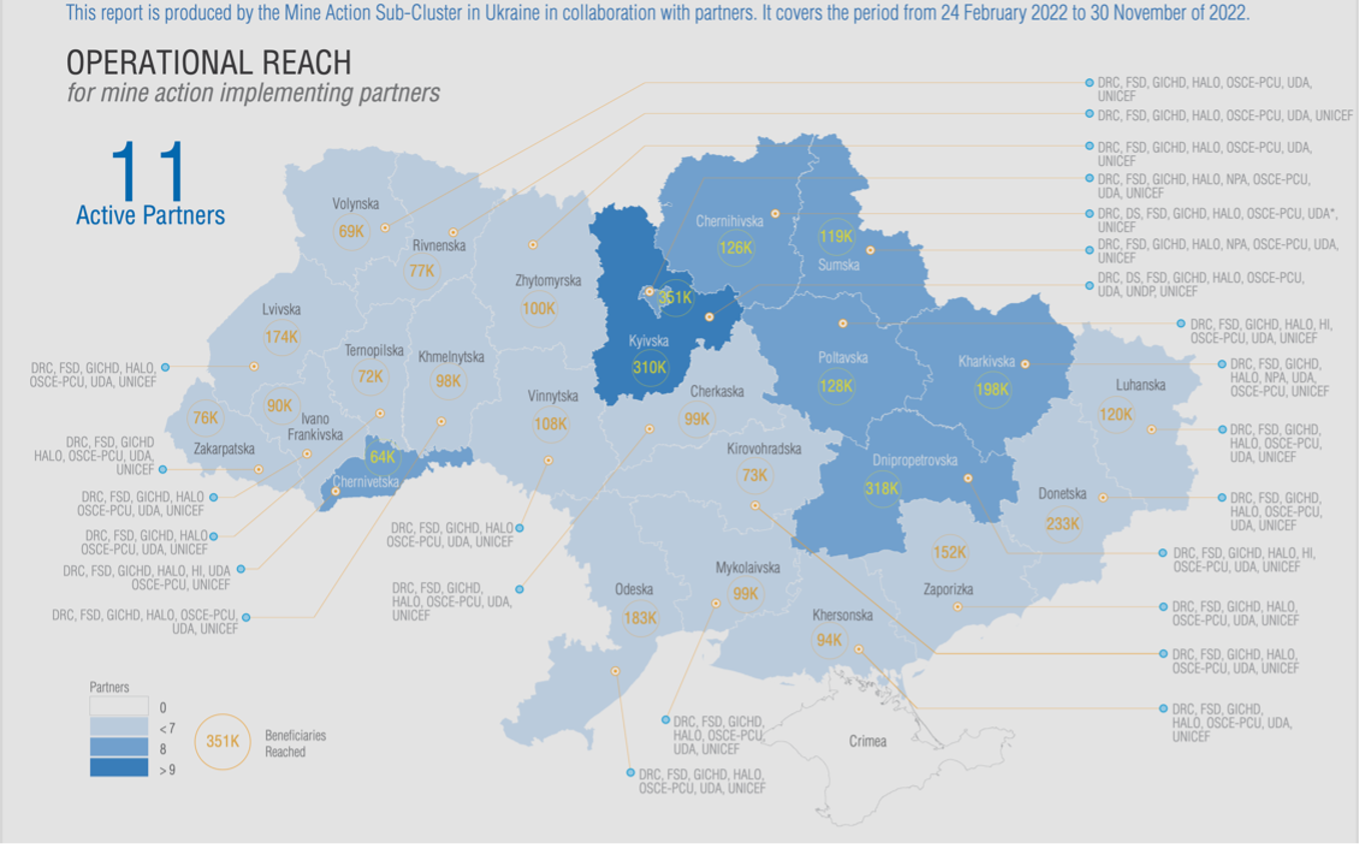

Nevertheless, EORE has continued to be undertaken where teams can gain access. A snapshot of the scale of these efforts are summarized in the document produced by the UN OCHA /Reliefweb in December 2022, which is shown below.

The extent of this activity is admirable but as a number of studies, such as that conducted by the German foundation Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) have shown, it is often hard to gauge the true impact of EORE programs. Most evaluations focus more on the output of the service provider, the numbers of people who have attended training, or how many sessions were delivered.

It is much harder to quantify how much of the training content the audience has absorbed. As the saying goes: “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” In post conflict areas the true measure of a program’s success correlates with a noticeable reduction in explosive casualties after the EORE training.

EORE programs must also ensure that the appropriate target audience(s) are identified. A 2007 review of EORE programs in the former Yugoslavia observed that the noticeable reduction in casualties among children was not matched by a drop in incidents involving adults; in fact, in rural areas there had been sharp increases in casualties. The simple truth was that it was easier to get donor funding for EORE programs aimed at kids, even when the risk to them was lower, than it was for training adults of all ages. Yet the adults were at greater risk for having to enter mined areas for economic reasons, such as harvesting crops, gathering wood, grazing animals, etc. EORE providers quickly altered their focus as a result of the assessment and the situation subsequently improved.

UNHCR reports that in Ukraine there are over 15 million internally displaced persons (IDP) and around 8 million who have left the country. While those who have “stayed” will receive, or at least should be receiving EORE training, the millions who escaped Ukraine completely or those internally displaced persons (IDP) who took refuge in “safe areas” will require “enhanced sensitization” towards the problem if and when they return home.

We can’t guess what proportion of those will return when the war ends, but experience in other war zones suggests many will as soon as the fighting is over. The provision of EORE to such large numbers of people in a timely fashion will be a challenge – but it must be done, somehow, to keep the casualty numbers already experienced from increasing when the fighting stops.

Victim Assistance

Article 6 of the Anti-personnel Mine Ban Convention obliges states parties to provide assistance for the care, rehabilitation, social and economic reintegration of victims of landmines and ERW by meeting the immediate and long-term needs of mine accident survivors, their families, mine-affected communities and the disabled.

This is, of course, easier said than done, especially while hostilities are ongoing. Following the 2014 invasion, Ukraine realized that, while in peacetime it had improved primary medical and emergency health services capabilities, it needed further assistance in the rehabilitation of trauma victims; initially for its military casualties but later for injured civilians as well.

In September 2014, at a meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Commission in Wales, medical rehabilitation was identified as a key area for NATO cooperation. A Partnership for Peace (PfP) Trust Fund was set up to provide medical rehabilitation services and equipment to support injured Ukrainian military and civilian defense personnel. Funds were also made available to help support the 15 team members who represented Ukraine at the 2017 Invictus Games.

The NATO PfP Medical Rehabilitation Project.Photo Credit: NATO Press Office

The NATO PfP Medical Rehabilitation Project.Photo Credit: NATO Press Office

Since the start of the 2022 Russian invasion, Ukraine has built upon the base capability provided by the Trust Fund with assistance from over 270 organizations, including a wide range of medical NGOs, such as Doctors Without Borders and the International Medical Corps, as well as donations and volunteers from individuals and small, ad-hoc, organizations throughout Europe and beyond.

In addition to the physical injury inflicted on thousands of Ukrainians, it is estimated that many Ukrainians have, or may develop, mental health conditions because of the horrors they have witnessed or the trauma of the situation in which they find themselves.

In an address to the 75th World Health Assembly Olena Zelenska, the First Lady of Ukraine, highlighted the mental stress experienced by Ukrainians because of the war in Ukraine.

In response, the World Health Organization has put forward a plan to control and coordinate mental health and psychosocial support services in Ukraine. This was formally launched, in December, by the First Lady and Ukraine’s Prime Minister, Denys Shmyhal. As with all issues arising from the effects of the war, the securing of sufficient resources to support the initiative will be essential to successfully tackling both the obvious physical injuries of victims and their hidden, mental health.

Advocacy

The United Nations encourages all nations to accede to international agreements that ban or limit the use of landmines and certain other conventional weapons. Adherence to the agreements is monitored and reported on, at regular meetings of “states parties” to the treaties.

The most important of these agreements are:

· The 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; the “Antipersonnel Mine-Ban Treaty” – Ukraine ratified accession in December 2005; Russia has not signed up.

· The 1983 Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons, focuses on the use of booby-traps, incendiary devices, blinding laser weapons and clearance of ERW – both Ukraine and Russia ratified membership in June 1982, albeit as part of the Soviet Union. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, Russia has resisted attempts in the intervening 40 years to add a compliance mechanism to the convention to ensure parties honor their commitments.

· The 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, prohibits all use, production, transfer and stockpiling of cluster munitions – neither Ukraine or Russia are signatories to the convention. It is reported that cluster munitions, most of which have both an anti-personnel and anti-vehicle function, have been widely used by both sides in the ongoing conflict.

Stockpile destruction

Article 4 of the Anti-personnel Mine Ban Treaty, commits State Parties to destroy their stockpiled mines within four years after their accession to the Convention.

Ukraine signed the Mine Ban Treaty on Feb. 24, 1999 and ratified it on December 27, 2005, becoming a State Party on June 1, 2006. In February 2002 a project was launched for the destruction of “PMN” APL at the Donetsk Chemical Plant, a munitions manufacturing facility. The project kicked-off with an official opening ceremony performed by the then NATO Secretary General George Robertson and the then Governor of Donetsk Viktor Yanukovych. A total of 4,000 mines were destroyed by May 2003. An interesting side note to this is that the bodies of the destroyed mines were used to make children’s toy Pelicans, which were donated to local orphanages and representatives of donor nations. Today, in fact, if you visit NATO Headquarters in Brussels, you will still see Pelicans on the desks of some ambassadors.

The NATO PfP Project for APL Destruction in Ukraine.Photo Credit NATO Support and Procurement Agency

At the 19th meeting of the States Parties in Geneva on Feb. 23 2021, Ukraine reported that it was unable to fully meet its obligation in regards to the destruction of its APL stockpile because of its overall lack of resources. It was able to declare that it had destroyed about 3.4 million anti-personnel landmines (APL), between 1999 and 2020, but that it still needed to destroy 3.3 million PFM-1 APL; the so called “butterfly mine.”

A report in the Canadian newspaper “Globe and Mail,” on Jan. 31, suggested that Ukraine had used some of this PFM-1 stockpile against Russian troops in Izyum, a claim denied by Ukraine. It is known that Russia has continued to lay large numbers of both manually laid APL as well as scatterable mines, including the PFM-1.

The PFM-1 APL.Photo Credit CAT UXO

Landmine (and ERW) clearance

On ratifying the Mine Ban Treaty, a state takes on the commitment to clear all anti-personnel landmines (and other ERW) on territory they control within 10 years. Many states parties have been unable to meet this obligation, either because of a lack of resources, the size of the contamination problems faced or, as in Ukraine’s case, war within their borders.

Landmine clearance is a complex, many-faceted task and is generally considered in two separate areas: military and humanitarian.

Military mine clearance is solely based on the need for the immediate, speedy clearance of safe paths to enable troops to advance and for military operations to proceed. In military parlance this is referred to as “breaching,” which often involves the use of devices such as mine plows and explosives in the form of explosive-filled hoses deployed by a rocket. While the aim is to achieve clearance in a manner that minimizes military casualties, the residual threat to others, who may access the area afterwards, is often given little thought. Troops will ignore and leave behind mines that aren’t in their way as well as damaged, dangerous mines in the cleared lanes. For this reason areas that have been subjected to military action of this kind can pose particularly serious threats to the community later on.

Example of a military mine plow vehicle.Photo: Pearson Engineering

Example of a military mine plow vehicle.Photo: Pearson Engineering

Detonation of a mine clearing line charge (explosive hose)Photo: U.S. Army National Guard Spec. Jacob Hester-Heard

Humanitarian mine clearance programs, on the other hand, must be more measured operations. The aim is to clear all explosive hazards from contaminated land so that civilians can return home safely and resume everyday life. Humanitarian demining is, by definition, slower, more resource intensive and, therefore, more expensive than its military counterpart.

Humanitarian demining: manual APL clearance.Photo: Natacha Pisarenko/AP Photo

Humanitarian demining: manual APL clearance.Photo: Natacha Pisarenko/AP Photo

The details of what a demining clearance program entails, including the processes, options available and technological developments, will be addressed in a separate article.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter