Carl Sagan was one of the most brilliant scientists and communicators of modern times who dedicated himself to exploring the wonders and mysteries of the cosmos. This popular genius was an in fact an American with Ukrainian roots.

Sagan, a handsome and eloquent man and unconventional scientist, was always ready to share his knowledge, curiosity and hypotheses about space and the place of earth and mankind within its unfathomable vastness. In doing so, he had no qualms about challenging authority, superstition and the prevalent ideologies of his day in order to help mankind better understand itself, its potential and limitations.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

During the politically tense and frigid days of the Cold War between East and West, Sagan demonstratively reached out to a fellow scientist with similar interests who was also courageously defiant given the constraints imposed by Soviet rule – the Ukrainian-born astrophysicist Iosif Shklovsky. Both men had Ukrainian-Jewish roots, were outspoken, and strongly believed in extraterrestrial life.

Sagan was born in 1934 in Brooklyn. His father, Samuel Sagan, was an immigrant garment worker from Kamianets-Podilskyi who had married Molly Gruber, the daughter of another Jewish immigrant from present-day Ukraine, from Sasiv near Lviv. A gifted and highly curious child, Sagan obtained a PhD in astronomy and astrophysics from the University of Chicago. After researching and teaching at Berkley and Harvard, he became a professor at Cornell University.

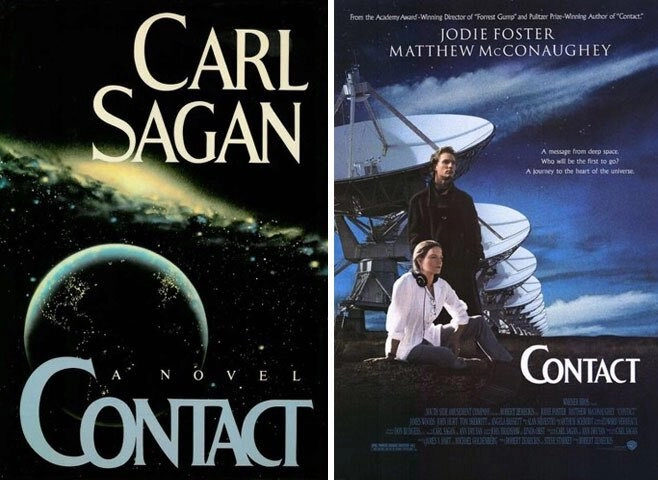

Apart from academia and scientific journalism, Sagan served as an adviser to NASA and helped develop its missions to explore the solar system. He was particularly active in advancing the case for believing in extra-terrestrial life. His fictional work on this subject called Contact was in 1997 made into a film starring Jodie Foster. He was also a consultant on Stanley Kubrick’s classic film “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Sagan wanted to make the basic ideas and questions obsessing him as an astrophysicist and humanist comprehensible to the general public, to raise awareness and stimulate debate. He found the perfect vehicle for this when, in 1980, a wonderful 13-part series called “Cosmos,” which he wrote and presented, was shown on American television. Its purpose, as he put it, was “to bring science to the public in an accurate and enthusiastic manner.” With its innovative video effects, novel and candid approach, masterly script and the charisma and persuasiveness of Sagan himself, the series was a huge success and remains a masterpiece.

Sagan’s down to earth approach and views won him fame and admiration, but also made him enemies among the more conservative scientific community. His use and advocacy of cannabis shocked some, and his dismissal of religion from an existentialist position as an obsolete superstition alienated religious fundamentalists.

But the issue which rankled the establishment most was Sagan’s outspoken opposition against the development of nuclear weapons. Their use, he warned in 1983, would result in a devastating “nuclear winter” threatening the very existence of “our civilization and species.”

Sagan’s prose in his numerous works on complex questions fusing science, philosophy and existentialism was a model of clarity, engaging and often almost poetic in style. In 1978, he won, among other awards, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction.

The pale blue dot

One of Sagan’s most famous quotations is from the TV series “Cosmos” when he compares earth as seen from outer space to a “pale blue dot.”

“Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it, everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives…every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam…”

And from this poignant observation, Sagan summarizes his philosophy: “Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.”

In this spirit, Sagan defied the ideological and military barriers diving East and West in those days and sought “contact” with a scientific colleague and kindred soul – Shklovsky.

The renowned Soviet astrophysicist was born in the eastern Ukrainian town of Hlukhiv in 1916, studied in Moscow and was based at the Sternberg Astronomical Institute. He also believed in extraterrestrial intelligence and wrote a book on the subject in 1962. Shklovsky wrote at the time to Sagan: “The probability of our meeting is…smaller than the probability of a visitation to the Earth by [extraterrestrial] astronauts.”

Eventually, despite the problems they had to overcome, the two distinguished scientific visionaries were able to cooperate. In 1966, Shklovsky’s manuscript was translated into English and Sagan wrote extensive annotations for it. Shortly afterwards, Shklovsky was allowed to travel abroad and finally met Sagan in New York.

Unfortunately, Sagan’s life was unexpectedly cut short when he was in his prime. The great popularizer, who brought science to the general public, died in 1996 at the age of 62, after a two-year fight against myelodysplasia (bone-marrow syndrome).

Shortly before his death, Sagan and his third wife, Ann Druyan, wrote a book that was planned as the first in a multivolume series. Sagan, inspired by Sergei Paradjanov’s classic Ukrainian film, gave it the same title: “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: A Search for Who We Are.” Paradjanov and the author of the novel that inspired the film, Mykhailo Kotsiubinsky, would have been proud of Sagan’s nod in the direction of Ukraine, its culture and his family’s origins.

This article was originally published in the August 2019 issue of Panorama, the in-flight magazine of Ukraine International Airlines.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter