Malcom Muggeridge showed up in the Soviet Union in 1932 as a foreign correspondent very much primed to be a Western supporter of the Great Communist Experiment. Practically all the foreign press corps was perfectly happy not to investigate the mass famines killing millions of ethnic Ukrainians and other Soviet citizens, as the state collectivized agriculture.

By background and class, he should have been one of them. Muggeridge was a Cambridge graduate, a practicing left-wing journalist. His father was a mild Socialist, and the Muggeridges had lived in Egypt and India and seen British-enforced discrimination and exploitation there first hand. At home, Muggeridge grew up in the English industrial heartland, enjoying a privileged, leisurely and comfortable life amid massed poverty and unemployment all around him, as the Capitalist system had apparently betrayed a working class eviscerated by service in World War I and now unemployed.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

But real life was different. Muggeridge was one of the very few Western journalists who tried to report on the famines. The Kremlin had all manner of means preventing foreign reporters from confirming the fact of mass murders, and his editors at the Manchester Guardian weren’t much interested. Like much of the Western elite of the day, some of his bosses thought Capitalism was dead and Socialism was the hope of mankind. Others pointed to mainstream reporting as proof he didn’t know what he was doing.

‘All of Us in Europe Need Ukraine in the Alliance’ – Ukraine at War Update for Oct. 4

Muggeridge thought the idea that the Communists in charge of Russia were up to any good was an outright lie and that people who bought that story were fools, which was why, he said, he wrote the book.

“I took a great dislike to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, and, even more, to its imbecilic foreign admirers.”

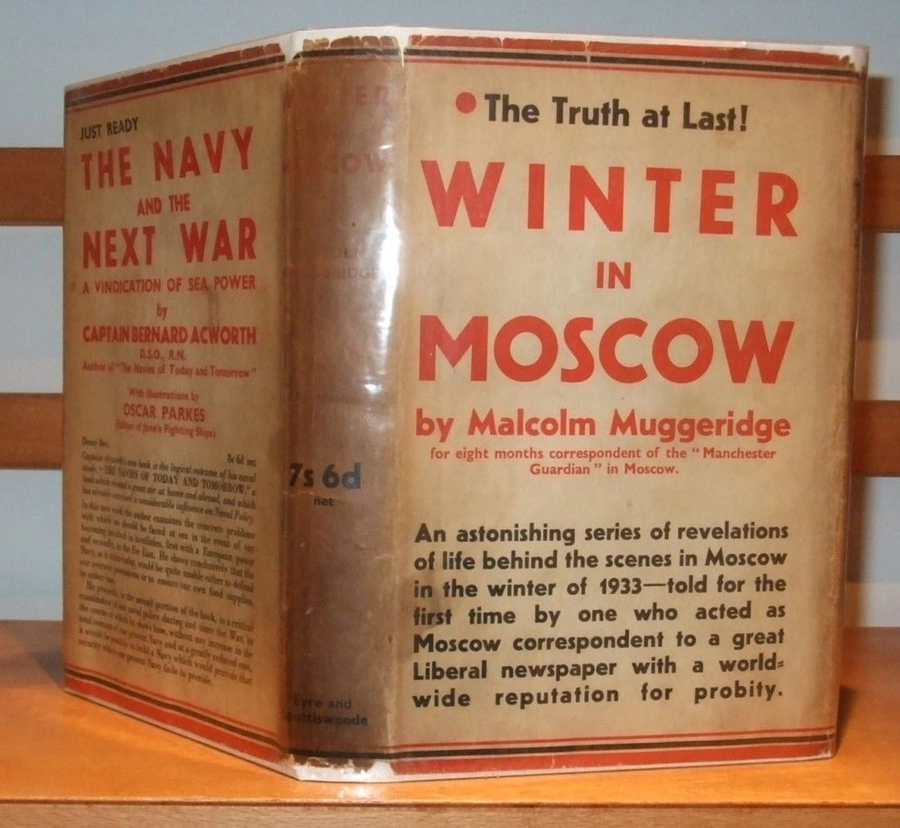

Winter in Moscow was published in 1934, is 252 pages and has been out of print for decades. Amazon sells the paperback for $473. The book is less plot-driven than a gold mine of thinly fictionalized vignettes drawn from Muggeridge’s time in the Soviet Union. His biggest target, widely speaking, is the cynicism and careerism behind the Bolshevik takeover of the country, which he calls the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

In one of the most telling character sketches a former soldier during the Revolution is destitute, on the street and playing an accordion for food money. Chatted up by foreign reporters, the man ticks off ideals he fought for that the Communists never delivered: free elections, secret ballots, liberation of political prisoners, the right to form trade unions, and the same food rations for all citizens. The press pack gets bored with him and hurries off for the official tour of a new Soviet hydroelectric plant.

Feud with Walter Duranty

Very near Stalin and his henchmen, for Muggeridge, were the mendacious and frequently substance-dependent Western journalists and Socialism groupies infesting Moscow in the 1930s.

One of the most notorious members of the Stalin-era Moscow foreign press corps, New York Times foreign correspondent Walter Duranty, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1932, during the height of the famines killing millions of Soviet citizens and known now as the Ukrainian Holodomor. The thrust of Duranty’s reporting, now obliterated by the historian Robert Conquest and others, was that Soviet collectivization was proceeding well and that the Russian people thought well of Socialism.

Muggeridge was later to call Duranty “the greatest liar of any journalist I have met in 50 years of journalism.” In the book, given the surname “Jefferson,” Duranty is an alcoholic dissipate unconcerned with facts and so in step with Kremlin messaging that his articles are literally dictated by TASS. Muggeridge’s barbed recollections of Jefferson/Duranty bear repetition at some length:

“Jefferson” explaining, in broad American, why collectivization and massed killings by starvation made good sense, because it punished rich peasants keeping harvests from the Communist state:

Gettinaway with everything. Gettinaway with murder. Gettinaway with the harvest. Gettinaway with everything just as they always have and will. Big country. Big, big country. Lots of people. Millionsanmillions of people. What’s it matter a few millions more or less?

Jefferson/Duranty on dictator Joseph Stalin and the Russian Revolution:

Stalin was different. He had never chattered away evenings in dingy lodgings, or spent indigestive afternoons playing chess in cafes in Paris or Vienna, or loitered, a proletarian rentier or remittance man, by the Lake of Geneva. He could be, and remain, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat because he so utterly hated and despised the Proletariat. Product of a Jesuit seminary; home-bred Napoleon content with domestic conquests; class-war Napoleon, pogrom Napoleon, he had the sense to see that the only purpose of the Revolution was to make someone… Tzar, and seeing this, to make himself Tzar.

In one vignette, a Jewish Communist functionary named Babel raids a Christian woman’s house in the Kuban grain belt region, and a Mongol soldier uncovers the family’s last bag of flour hidden under a sleeping grandfather. The man is marched off to be shot and Babel promises to search the premises again the next morning. The woman kills her sleeping children with an axe and then, when Babel returns, murders him. A Communist named Kokoshkin, a newspaperman working for Pravda, cleverly spins Babel into a state-sanctioned hero, the woman into an oppressor of the working class, and publishes a feature article explaining to readers why grain confiscations need to be stricter.

“Comrade Babel must be numbered among our blessed dead; but we, the living, will see to it that his death shall not have been in vain,” reads, in part, the press release Kokoshkin hands the Moscow foreign press corps. Then Kokoshkin gives Jefferson/Duranty an “exclusive” interview.

Jefferson/Duranty’s telegraph to New York with the latest Russia news reads:

Last night addressing collective farm shock workers Kokoshkin stressed necessity ruthlessly crushing opposition kulak elements to governments collectivization policy stop bolsheviks determined harmonise agricultural economy with industrial development plan stop admittedly involves cruelty and casualties but dash putting it brutally dash impossible to make omelettes un-cracking eggs…

The worst part about Muggeridge’s book is that such anecdotes, although without question an accurate rendition of how the Western press reported the Soviet grain famines, are fictionalized, offering the negligent and criminal the fig leaf of deniability. One suspects a shorter book naming names, dates, specific news items and instances of bottles of vodka consumed would have forced, by now, the New York Times to return Duranty’s reporting prize back to the Pulitzer board.

Scathing portraits and devastating wit

Chapter IV – “Ash-Blond Incorruptible” – contains 21 pages of some of the English language’s most acerbic and at times funny send-ups of a big-time parachute reporter getting a huge international story (the famines) absolutely wrong. In some places, the satire is on par with Evelyn Waugh’s classic on the subject of foreign correspondent amateurism, failure and negligence, Scoop, published in 1938.

Muggeridge tells the tale of a London reporter working for a “great, Liberal newspaper” (very similar to the real-life Guardian), named Wilfred Pye, who is summoned into his editor’s office and told to find out whether or not there is a famine in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet ambassador in London, a civilized and pleasant man, plies Pye with brandy and explains that “difficulties” are not “famine.” Pye travels to Moscow and observes how people there seem fine, noting that his restaurant meal was excellent. He then interviews a “local expert,” a fellow Englishman living in Moscow, graciously offered to him by the Ministry of Propaganda. The word “from the ground” is clear: no famine.

But Pye is handsome, blond, committed to ferreting out the truth, and employed by a “great, Liberal newspaper” dedicated to exposing the misdeeds of those in power. Pye marches off to a Moscow street market and observes starvation and a food riot. He concludes Soviet citizens are being exploited by food speculators.

On a train to Ukraine he winds up, coincidentally it seems, sitting next to more than one English-speaking Russian, who tell him famine is a fantasy. His car breaks down in an empty village whose last surviving resident tells him of mass starvation and forced deportations. Pye writes that off to the exception proving the rule. His story later incorporates glowing agricultural production statistics from the Propaganda Ministry staffer Kukushkin.

Pye’s articles in the great English Liberal newspaper were widely read and widely quoted. Now at last, readers of the articles thought, we know what is really going on in Russia. It’s a great comfort to think that there’s at least one newspaper left that gives a balanced, objective, unprejudiced account of things.

Muggeridge’s venomous character portraits often attest to the fact that, even a near-century ago the capital of Russia, more than possibly any other place on Earth, held a peculiar attraction for intellectual weirdos with flexible morality, who somehow found employment as journalists.

Beatrice Canning, daughter of a medical doctor who moved to Moscow, finds herself recently hired as a “foreign correspondent” aboard a sleeper train to Ukraine and wondering about male attention. Mr. Trivet, an Englishman, enters her coupé and initiates a philosophical discussion about the Socialist doctrine of Free Love. The conversation is progressing well when Professor Seabright (“He was a large, white, soft man, the lower part of whose face seemed to be disintegrating as though it had been attacked by some venomous parasite”), appears at the door, is glad to find clever people to talk to, and holds forth at some length about dysfunctional marriage traditions in the US. After inspecting his watch several times with no effect, Mr. Trivet forces Professor Seabright out of Miss Canning’s compartment in mid-sentence. All three later report positively on the hydroelectric dam.

Lord Edderton, a convinced Communist and declared enemy of his own class (albeit travelling in a personal train car) tours Russia, learns “the truth,” and appears at the House of Lords. Peppering his speech with aristocratic defects, Edderton tells of industrial wonders on the Dnipro River and the glories of Socialist industrialization. Unfortunately for poor Edderton Britain’s elite seem bored.

“You may be indifferent now,” he shouted, a lisping prophet; “but when the pwesent cowupt social order falls about your ears, and the iwesistable forces of wevolution surge up to engulf you, then you will wealise the magnitude and significance of what has been achieved in Wussia.”

Near him sat a trade union leader given a peerage by the last Labour Government. The man had an enormous red face; and he was laughing at Lord Edderton’s speech. His huge stomach and the folds of his chin were shaking as he listened to it.

Gleefully drawn, characters, usually wealthy and rather stupid, appear and disappear in Muggeridge’s book continually.

A well-bred English lady named Mrs. Triviet buttonholes a Kremlin Propaganda Ministry staffer named Aarons about a sensitive subject in her particular fields of interest, Socialist health care and women’s rights:

Mrs. Triviet bore down on them, bare pink legs swelling out of tweed skirt; heavy breasts quivering, pale eyes lost in a soft vague face.

“Oh, Mr. Aarons,” she said breathlessly, “can you tell me about abortions? They’re free, aren’t they?”

“Not exactly free,” he corrected; always precise; always ready to admit failings where they existed; “but within everyone’s means; and of course, carried out in State hospitals by the most up-do-date-methods.”

“Do you do foreigners?”

Mr. Aarons looked a little anxious. Her figure was inconclusive.

“There are certain formalities,” he said. “If you’d care to visit one of our State abortion centres…”

“I should,” Mrs. Trivet said rapturously; “Tomorrow.”

Anecdotes and tales aside, Muggeridge concludes:

The result is that news from Russia is a joke, being either provided by men whose long residence in Moscow has made completely docile, or whose particular relationship with the Dictatorship of the Proletariat puts words into their mouths, or by men who, while trying to say more than they can, are forced, for interested and quite legitimate reasons, to be discreet.

In consequence of all this, the credulous organs of the Left in England are systematically misinformed about Russia, while the credulous organs of the Right, lacking genuine information, make their case against the Dictatorship of the Proletariat by overstatement and invention.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter