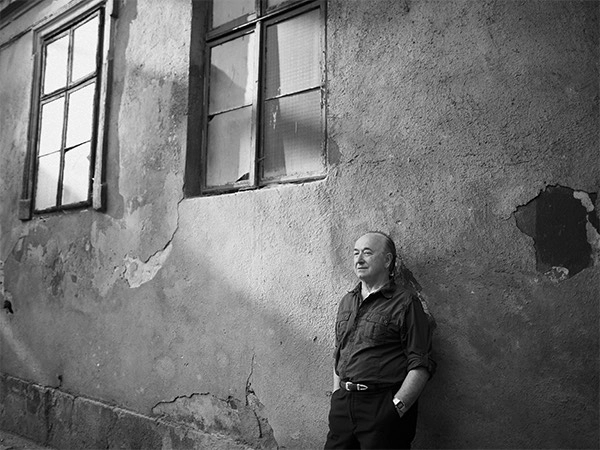

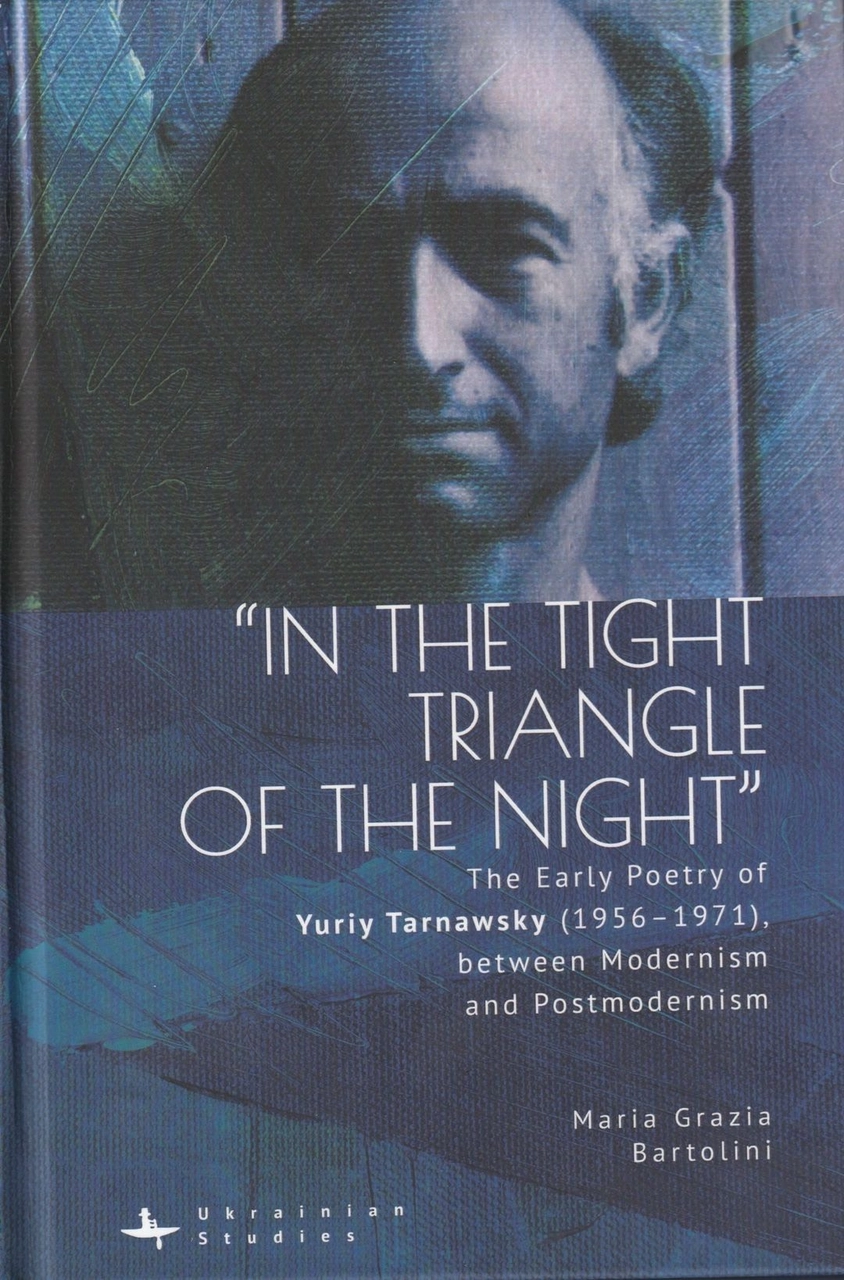

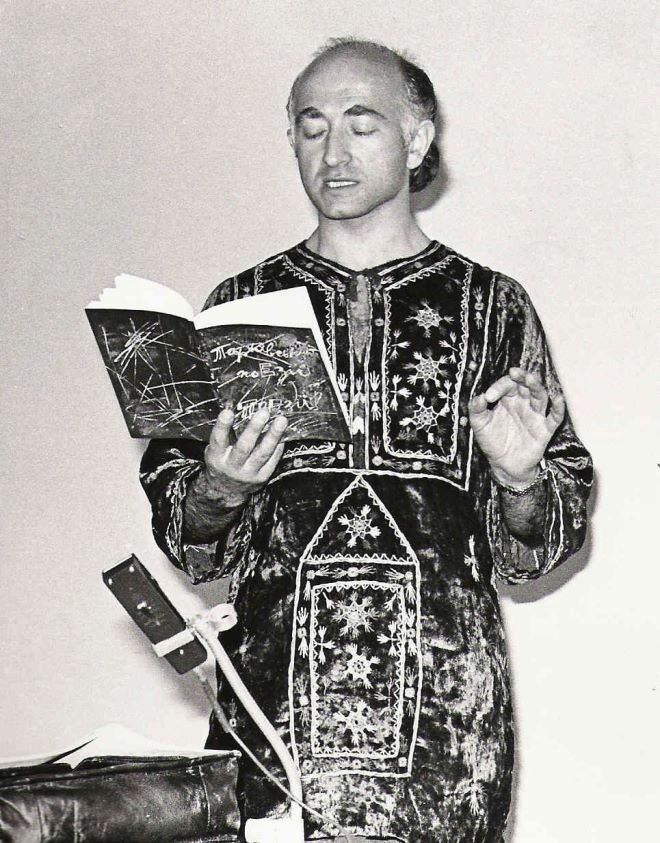

Editor’s note: With the publication of In the Tight Triangle of the Night, by Maria Grazia Bartolini, which examines Yuriy Tarnawsky’s early Ukrainian-language poetry, the writer celebrated his 90th birthday. Kyiv Post is publishing a presentation given at the symposium Running Barefoot Home held on Tarnawsky’s work at New York’s Columbia University in October 2023.

Separation

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Since the full-scale invasion on Feb. 24, 2022, I’d been thinking about Yuriy Tarnawsky’s work a lot. In particular, some very specific images from one of his most recent novels, Warm Arctic Nights. It might be his most autobiographical work of fiction, and toward the end there are some harrowing scenes in a train and around a train station. But I won’t spoil it for anyone.

In 1944, when he was still a 10-year-old boy, Tarnawsky was uprooted by war, World War II – a war that impacted all Ukrainians then, but especially those forced to leave their homes and settle elsewhere.

The novel – recounted in the form of a questionnaire – is essentially a decent into hell on earth.

The narrator, who answers a series of seemingly innocuous questions, describes an idyllic childhood, relations with parents, relatives, and the world outside the home. Then the war comes, and the boy is separated from everything he knows: mother, father, home, language, love.

If hell is a deep separation or “alienation” from all that is good, then Warm Arctic Nights is the depiction of a boy’s steady descent into hell on earth.

I had that novel fresh in my mind during the first weeks of this current war.

New York’s Ukrainian Museum: Opening Out and Taking Back

When Ukraine started getting bombed, I tried to go there as soon as I could. I wanted to help. So I found a charity organization that helped refugees just over the border with Poland. I wound up chopping vegetables and handing out meals to the waves of refugees coming into the Przemysl train station from Ukraine.

The images were unforgettable. Literally thousands of mostly women and children, often with their dogs. Wave upon wave of them, still in shock, carrying their lives in bags – just like I’d imagined from Tarnawsky’s novel.

I helped at the border for a while, then took a train to Lviv, improvising as a translator for a surgeon who wanted to volunteer his skills.

On the various train rides first from Krakow to Przemysl and then from Przemysl to Lviv, I passed by Tarnow and Rzeszow, the towns near where Tarnawsky had spent his childhood. And I knew from reading history and talking to people from there that the entire area hadn’t always been as ethnically homogeneous as it was just prior to this war. That part of Galicia (Halychyna) had been leopard-spotted with Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish communities, and I tried to imagine what the villages and countryside were like just before World War II, as they’re described in Warm Arctic Nights.

But the images of mass exodus by train stuck with me. And I believe they’re key to the personal mythology of many Ukrainians forced to leave – during World War II and now again. At least six million people are estimated to have left Ukraine in the past two years, and another eight million have been displaced within Ukraine – that’s one third of the population uprooted.

World War II, with all its implications, is perhaps the prime formative event of Tarnawsky’s work. And even with most of his works written in times of peace and prosperity, the war echoes through all of it.

I’ve described Warm Arctic Nights as a decent into hell. And for our purposes, let’s define hell through the etymological root of the word “diabolic”; “diabolos,” comes from the Greek diaballein, which literally means “to throw apart,” splitting, separation, disintegration (whereas symbolos means bringing together). So hell, for our purposes, is a deep, psychic, existential separation or “alienation” from all that is good. And in that sense, Warm Arctic Nights is a masterful depiction of a boy’s steady descent into hell on earth.

Rebellion

After reading Warm Arctic Nights and seeing the current war on Tarnawsky’s turf, as it were, I came to understand his entire body of work as a rebellion of sorts, partially against this vague sense of separation I define as hell, but not only.

That sense of rebellion in Tarnawsky’s writing had an important impact on myself as a poet and writer.

I first met Tarnawsky and became aware of his work in the early 1990s. I’d been translating the poetry of Vasyl Barka and visiting Barka regularly. Through Barka, I came to the attention of Bohdan Boychuk, who introduced me to Tarnawsky and a host of other Ukrainian writers.

I’m too young to remember the New York Group – founded by Tarnawsky and Boychuk – when it was active as a “group,” but I became familiar with their work while they were still writing, even though each member had gone off in their own direction.

Tarnawsky’s voice is instantly recognizable and consummately inimitable. He is a master at undermining the reader’s expectations.

I was immediately drawn to Tarnawsky’s work, especially the experimental English-language prose of Meningitis.

For those unfamiliar with Vasyl Barka and other Ukrainian writers in the diaspora during the 1990s, suffice it to say that if any two poets were on opposite ends of the spectrum, then it was Barka and Tarnawsky. Yet those were the two who attracted me most. Why? Because of what they had in common: both voices are instantly recognizable and consummately inimitable.

In his seminal 1950 essay “Projective Verse,” Charles Olson lays out the “principle”: FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENTION OF CONTENT.

When I came across Tarnawsky’s work, with all its formal experimentation, I tried to extrapolate a sense of content, and it opened a labyrinth of possibilities for me.

Back then I had a deep sense of literature and the writer’s task as using language, lyric and narrative to change the reader’s perception of reality. And one of the primary tactics by which to effect that change is to undermine the reader’s expectations. Tarnawsky is a master at undermining the reader’s expectations. But more on that later.

I even wound up trying to imitate Tarnawsky with a series of absurdist stories and vignettes that had a similar echo of Gogol, Beckett and Surrealist painters. But you can’t try to imitate a writer like Tarnawsky. Ultimately, he’s too original, too idiosyncratic. At best, any attempt at imitation should drive you to find your path and manner of either undermining a reader’s expectations, or, conversely, seconding them.

So I put both Tarnawsky and Barka down for over a decade. I wound up working as a journalist, whereby I developed a sense of attention to real events and how they’re perceived through a filter of consensus objectivity. I also worked as a translator, which inevitably hones an attention to linguistic form.

Then, out of the blue, around 2020, I was approached by an Italian-born scholar of Ukrainian history and culture, Maria Grazia Bartolini, to translate her study, written in Italian, of Tarnawsky’s early poetry in Ukrainian. [The book, titled In the Tight Triangle of the Night, has just come out.]

I said “yes” immediately. “I’m a big fan of Tarnawsky,” I told her. So for nearly a year I had the pleasure of digging deep into all the earlier books in Ukrainian that Tarnawsky had written in the 1950s and ’60s, even translating some of the poems and getting under their skin.

Through these works I traced a genealogy of Tarnawsky’s rebellion within the context of the New York Group of poets. From his early interest in existential philosophy and modern art to his attempt at blowing certain paradigms of Ukrainian literature out of the water, Bartolini’s book plumbs the intellectual milieu of Tarnawsky’s early formal experiments.

But Bartolini’s study limits itself to Tarnawsky’s early poems in Ukrainian. It stops just when Tarnawsky made the decision to switch into English, which, I assume must have constituted a sort of psychic rebellion.

As anyone who has been brought up multilingually knows, there’s always a low-intensity war going on in your mind that gets pushed down into the subconscious somehow and co-opted by other cognitive functions.

Tarnawsky was born into a Ukrainian-speaking family, in a society where Polish was the official language of government, schools and the ruling classes – that is, until the Soviets came and brought in Russian. After leaving Ukraine as a refugee, he attended secondary school in German. Then, when he arrived in the United States, he studied at university in English. At a later point he even moved to Spain and picked up Spanish.

On top of all those languages, Tarnawsky worked as an engineer at IBM, so he had to be versed in all the earliest programming languages. Even more importantly, in the late 1950s and early 1960s he worked on a US-government project that enabled computers to translate Russian texts (a sort of proto-Google translator).

Later, he even picked up a PhD in linguistics.

In other words, Tarnawsky had a deep and intimate understanding of the building blocks of language, as well as the tensions and frictions they created on various levels – semantic, emotional, existential, and so on.

His experimental works were prophetically prescient. They explored, through literature, mechanisms that have transformed our world – the algorithmic structure of language’s impact on human emotions.

The struggle against literary conventions

With the fiction works Meningitis and Three Blondes and Death, he “engineered” an artificial language, which he characterized in an essay from Claim to Oblivion as: “a highly restricted language (strictly speaking, an artificial language which is a proper subset of English), developed as my reaction to being unable to justify the syntactic structure of sentences I had been using in my writing, as a sort of punishment for obtuseness – ‘If you can’t figure out this simple question, then suffer like this.’”

In the essay, he goes into minute detail about how he developed the language, and often pokes fun at himself:

“Regarding the language I engineered for the two books – it obviously is cold and devoid of emotions. Three Blondes and Death was characterized by one reviewer as being written in a language of autopsy reports, which pleased me greatly since this is the effect I wanted to achieve. I wasn’t planning for it to be like that in the beginning, when I decided to write the book in simple sentences, but it was perfectly suited for the story of monumental loneliness and alienation [a separation/descent into hell] that I was ultimately going to tell.”

But autopsy reports aside, what happens to me when I read Tarnawsky’s works from this period is at first a strange sense of language chugging along in a minimalist way, which can grate on your nerves as it undermines your expectations of what English prose should be like. It’s almost like reading computer code. But very quickly I become hypnotized – much the way, say, an elegant musical composition by Phillip Glass might hypnotize you – and enter into a disturbing groove in which I feel like I’m observing the mundane acts of average humans from the perspective of my alienated (dare I say, lobotomized) contemporaries.

In short, the narrative makes me change the way I perceive reality. I become hyperaware of the mechanisms behind alienation.

Tarnawsky became a noble literary insurgent – a freedom fighter, fighting for the freedom of the mind, the creative spirit.

Ultimately, these rebellious works by Tarnawsky were much more than a mere attempt to scandalize or “épater la bourgeoisie.” They were prophetically prescient, in the sense that they explored, through literature, mechanisms that have transformed our world (or poisoned it, some would argue) – above all, they explored the algorithmic structure of language’s impact on human emotions.

Artists are often described as the antennae of society, and I believe Tarnawsky was on to something genuinely terrifying. Intentionally or not, he was putting his finger on the very structure of consciousness that has facilitated this world of alienation we treat with pharmakological band-aids and simulacra of violence, to use a couple of postmodern concepts.

From rebel to insurgent

At some point, after he switched to English (often reverting back to Ukrainian, and then back and forth), Tarnawsky’s work seemed to reflect a reluctant acceptance of his position at the margins, lobbing Molotov cocktails into the mainstream of pop-literary culture.

Tarnawsky became, at least in my eyes, a noble literary insurgent (літературний повстанець) – a freedom fighter, fighting for the freedom of the mind, the creative spirit.

One could argue Ukrainians are doing the same, right now.

And nowhere is this position exemplified as clearly as in the 2013 collection of “heuristic poems,” Modus Tollens, which he subtitles: IPDs: Improvised Poetic Devices.

The thin strips of poetry – often just observational aphorisms – are littered with line breaks in mid-word, like little explosives on the side of the road forcing you be hyperaware of language’s (at least the English language) phonetic and phonemic nature. After scanning a few of these IPDs, the reader can no longer proceed down any familiar path, oblivious to what’s at the margins, because there might be something hidden in a scrap pile, or trash bin, or under the asphalt. You’re constantly keeping the corner of one eye fixed on what might be lying in the ditch, or under the weeds.

A similar insurgency occurs in his prose writing. After Three Blondes, Tarnawsky largely abandoned that restricted language, and in The Placebo Effect Trilogy he explodes with expressionistic “negative-text mini-novels” – sort of like a cross between Kafka and David Lynch on LSD.

And then, he comes full circle to produce Warm Arctic Nights, a straightforward memoir narrative you can’t put down for all its hellish emotional impact.

At the risk of belaboring the parallelism, I’ll conclude with my own little Molotov cocktail: War is a terrifyingly transformative process. Both in geopolitical and – especially in Tarnawsky’s case – literary terms.

Ultimately (as per Empedocles), Strife generates a transformative momentum of its own.

In Ukraine – where every day you can get hit by a missile, where the lives of one-third of the population have been uprooted and scattered, and nearly everyone has lost someone dear to them – you can’t take anything for granted.

The same goes for Tarnawsky’s work. You can not take anything for granted. And that can be very disturbing. Terrifying even.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter