NATO defines special operations as: “military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equipped forces using unconventional techniques and modes of employment.”

The Ukrainian Special Operations Forces (UASOF) motto “I’m Coming For You!” (Іду на ви!) was that of the tenth-century Ukrainian leader Sviatoslav ‘The Brave,’ a Grand Prince of Kyiv renowned for his bravery and his success in defeating armies that greatly outnumbered his own. In light of the situation Ukraine’s armed forces find themselves in today, the motto is ever more appropriate.

- Obtain the most current Ukraine news articles released today.

- Russian Losses in Ukraine

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

In his keynote speech to the 2023 Special Operational Forces Conference and Exhibition (SOF Week) the Commander of the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), General Bryan P. Fenton, talked about building special forces relationships with other countries and made special reference to the US relationship with Ukraine’s Special Operations Forces (UASOF).

His view seems to be that US special operations forces (USSOF) have taught Ukraine all they know but now the UASOF have shown the USSOF a thing or two they didn’t know which they are now putting into practice.

Where it all began

The first modern special forces unit was the Special Air Service (SAS), formed in July 1941 from the unorthodox idea of a British Army Lieutenant, David Stirling. He believed that highly mechanized forces relied so much on logistics to operate, that a small team of highly trained soldiers operating behind enemy lines could gain intelligence, attack enemy supply routes, destroy enemy fuel and ammunition dumps, destroy aircraft on the ground, and generally wreak havoc.

Americans Fighting in Ukraine Criticize Trump’s Treatment of Zelensky, Embrace of Russia

When fighting a largely defensive war the ability to project disruptive forces behind enemy lines and blunt their attacking ability now seems such an obvious strategy. The success of the SAS meant that the idea quickly caught on with all other armies. There are hardly any armed forces in the world that have not developed a special forces capability. None more so than Ukraine’s Special Operations Forces – although it nearly didn’t happen.

UASOF – a short history

Ukraine’s Special Forces Command was originally created from elements of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic’s ‘GRU’ [Military Intelligence] Spetsnaz. While they took part in some military operations, such as in Afghanistan, they were very much used, in the years immediately following the break-up of the Soviet Union, to support active, domestic military intelligence operations.

However, when the 2014 Russian invasion started, many Ukrainian regular forces were deployed around the world, in places such as Kosovo and Somalia. The government initially turned to former Ukrainian Spetsnaz personnel to defend Ukraine – and they did a reasonable job.

In 2007, Ukrainian Defense Minister Anatoliy Hrytsenko published a new doctrine for the creation and use of Special Operations Forces that would support conventional military operations rather than just be the executive arm of the armed forces ‘secret police.’

The Office of the UASOF and training centers were established, and links were formed with US and UK special forces. Despite this promising start, in 2011 the Ukrainian MoD decided to disband its Special Operations Forces for both financial and doctrinal reasons.

In September 2014, then-President Poroshenko decided to rapidly reform the UASOF, appointing the deputy commander and chief of staff of the Ukrainian airborne forces, Sergei Kryvonos, as the head of the Special Operations Directorate of the General Staff of Ukraine. By the end of 2014, the unit had around 4,000 operators ready to deploy or undergoing training.

In 2015, the UAF General Staff transferred control of the UASOF to the Ministry of Defense, which promptly decided to dismantle and reorganize the unit reducing its strength to 2,000 operators and issuing a new concept for Special Operations Forces in January 2016.

Major General Igor Lunyov was appointed as Commander of the new UASOF with Kryvonos as his Deputy and Chief of Staff. Three years later, one of the UASOF units, the 140th Special Operations Forces Centre, became the first non-NATO unit to be certified as a Special Operations Forces (SOF) unit eligible to join the NATO Response Force (NRF).

Lyunov was replaced as UASOF commander by Major General Hryhoriy Halahan in August 2020 and he in turn was replaced by the current commander, Brigadier General Viktor Khorenko in July 20022. Following Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, Ukraine increased the number of UASOF operators to around 3,000.

| Brigadier General Viktor Khorenko, Commander UASOFPhoto: UASOF Twitter

|

Current organization of the UASOF

The 2016 concept laid out the following structure for the UASOF:

[note: locations for units are as at peacetime and may no longer be current]

UASOF Command - Berdychiv, Zhytomyr region consisting of:

· 99th Command and Support Battalion

· 142nd Education and Training Centre

· Land warfare and special purpose units

Special reconnaissance and direct-action operations units:

· 3rd Special Purpose Regiment “Prince Svetoslav the Brave” - Kropyvnytskyi, Kirovograd region.

· 8th Special Purpose Regiment “Iziaslav Mstislavich” - Khmelnitsky, Khmelnitsky region.

· 140th Special Operations Forces Centre - Khmelnitsky, Khmelnitsky.

Aviation Special Purpose Unit:

· 35th Mixed Aviation Squadron - Havryshiyka Air Base, Vinnytsia region. This unit is mainly involved in the extraction, resupply, and rescue of UASOF teams.

Naval Special Purpose Unit:

· 73rd Maritime Special Operations Centre - Pervomaisky Island, Mykolaiv region.

This unit focuses on maintaining security in the Black Sea and also counterterrorism maritime missions.

Information and Psychological Warfare (IPW):

· 16th IPW Operations Centre - Huiva, Zhytomyr region

· 72nd IPW Operations Centre - Brovary, Kyiv region

· 74th IPW Operations Centre – Lviv

· 83rd IPW Operations Centre – Odesa

What does the UASOF do?

The Ukrainian concept for special forces operations envisages coordinated operations involving both UASOF and the conventional Ukrainian Armed Forces. The actual mechanisms for this are obviously sensitive but in outline UASOF tasks include:

· Operational raids behind enemy lines;

· Intelligence gathering including development of intelligence networks;

· Counterterrorism activities;

· Search, rescue and evacuation of hostages and prisoners;

· Cooperation with partner special forces units;

· Psychological operations;

· Support to drug and arms counter-trafficking operations;

· Training support to partner police and military forces.

Weapons and equipment

As is common with special operational forces worldwide, the UASOF has a vast range of weaponry and special equipment. Since the full-scale invasion, what was already an impressive arsenal, has been supplemented by high-quality, Western donated equipment.

The UASOF arsenal consists of semi-automatic pistols, assault rifles, sniper rifles, light machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, anti-tank guided weapons, man-portable air defense systems, defensive and offensive grenades, and a range of suppressors (silencers).

| Typical SOF weapons and personal equipmentPhoto: Reddit

|

UASOF are provided with the best quality equipment available, including personal uniforms, load carrying equipment, helmets, body armor, underwater equipment, overt and covert communications, thermal and other imaging equipment.

The UASOF have access to a wide range of vehicles and other forms of operational transport including small patrol boats, Zodiac-style small boats, high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles (HMMWVs), and a range of aviation support including helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.

UASOF actions against the Russian invasion

Many, if not most, of the operations that UASOF are called on to perform are shrouded in secrecy and will remain non-attributable, at least until someone writes a memoir after the war is over. There are, however, events that Ukraine has confirmed that involved SOF personnel and others that point firmly to their involvement.

Since the start of the war, UASOF sources have claimed responsibility for a number of special reconnaissance and direct-action operations targeting Russian personnel, materiel and infrastructure at the front line and behind enemy lines.

It is known that UASOF forces played a key role in defensive actions against Russian airborne forces that tried to seize Hostomel airport in the first days of the war. UASOF ‘held the ring’ until conventional Ukrainian territorial defense and regular forces could be organized and deployed to eventually dislodge the Russian paratroopers, after a battle that lasted for six days, much of which was filmed at the time.

In the early days of the full-scale invasion Russia’s lack of operational planning, lack of communications and poor military performance allowed UASOF to operate with comparative freedom. The epitome of this was the almost 60 km traffic jam that resulted when Russian forces from ten separate tactical units converged on the paved roads leading to Kyiv, because of the soft ground conditions in February 2022.

Here and in other areas, small UASOF teams armed with anti-tank weapons, initially rocket-propelled grenades, were able to ambush columns. They used, in hindsight, a simple tactic. A team would hit the front vehicle in a convoy, another team would hit the rear vehicle. The rest of the convoy either unable or struggling to maneuver would then be picked off almost at leisure by other UASOF teams. It got even worse for the Russians when anti-tank guided weapons, Javelin and NLAW, arrived from the West.

In the early months of the war, the UASOF were not used for special operations, but to replace ordinary infantry for missions that were considered to be critical. As more conventional Ukrainian forces were recruited, trained, and deployed to the front lines, which began to become more stable, the UASOF was released to play the role for which they had been created: leading resistance and sabotage efforts behind enemy lines.

UASOF operations and tactics are a direct extension of long-standing special forces doctrine. It is based on the deployment of small teams (typically 4-6 operators) to gather targeting intelligence for commanders and to conduct sabotage operations against targets of opportunity such as logistics trains, command centers, and high-value targets such as aircraft, ammunition dumps and fuel depots. This not only degrades the enemy’s military capability but also impacts his morale by spreading fear well beyond the front line.

In the current war, the UASOF is aided by: an ability to recruit human agents in Russia and the occupied territories; access to Western satellite, electronic warfare, signals and cyber intelligence; the possession of strike drone and electronic warfare technology that provides its teams the ability to deploy capabilities that Russian forces cannot easily identify, target, or engage; the poor levels of professionalism among Russian troops allotted to protect key assets; the motivation of Ukrainian special forces to operate at very high risk in defense of their country.

Starting in July and August attacks began to happen in both occupied areas of the Donbas and in Russian areas close to the border, which were undoubtedly the work of UASOF. This included the destruction of an ammunition storage site in Timonovo, a key logistics hub in the Russian oblast of Belgorod.

There were further attacks including on the Russian airfield in Stary Oskol, just 80 km from Voronezh, the headquarters of Russia's Western Military District. There were explosions at a number of sites around the Kherson dam, at the southern juncture of the Dnieper River, in the build-up to the retaking of Kherson in December. There have been reports of increasing numbers of explosions in occupied areas including across the Crimean Peninsula, which are seen as concerted efforts to degrade Russian command and logistics in advance of an anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive.

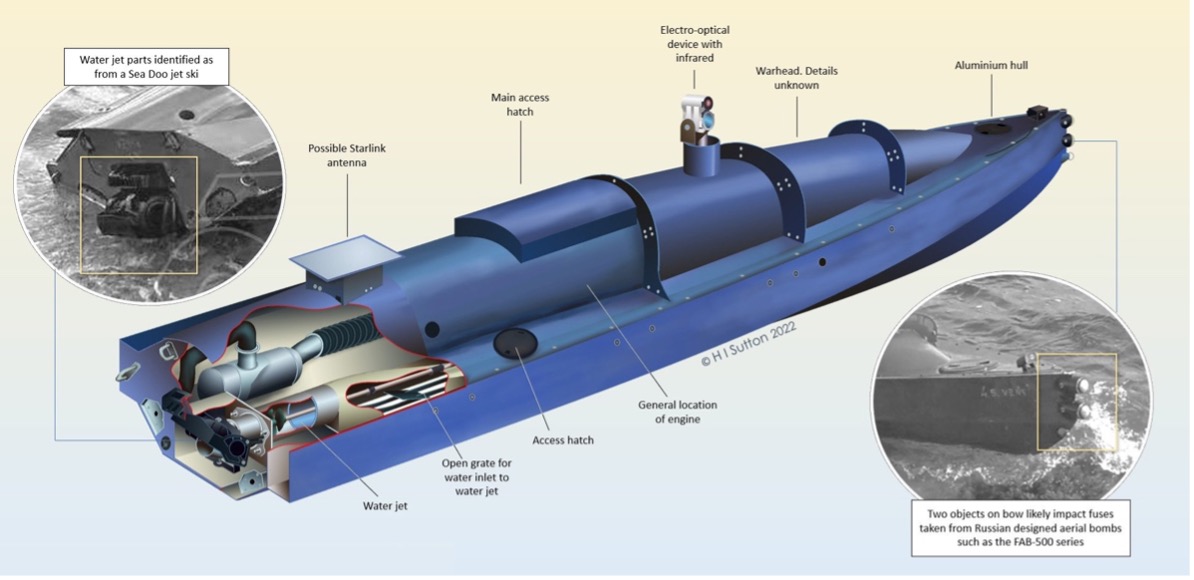

Other spectacular attacks, probably initiated by UASOF elements, include the October 8 attack on the Kerch road and rail bridge that links Russian-occupied Crimea with the Russian mainland which, over 6 months later, has still not fully reopened. The attack was also noteworthy because it seems to have been the first use by UASOF of uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), popularly known as the Kamikaze boat.

Ukrainian Kamikaze boat.Graphic: HI Sutton

The USVs are also believed to have been used in an attack on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in the Sevastopol naval base on the night of April 24.

Recent attacks on Russian territory including the improvised explosive attacks on key pro-Kremlin individuals Darya Dugina, Vladlen Tatarsky and Zakhar Prilepin and the drone attack on the Kremlin as well as more unexplained explosions, widespread fires, cut power lines and derailed trains have all been blamed on Russian anti-Kremlin ‘partisans.’ It is more than likely that these were actually carried out by UASOF operators or by Russian nationals who have been trained and equipped by them.

One of the (many) advantages UASOF, especially those of its members from the East and South of Ukraine, is that they not only speak the language of the enemy but also understand the mentality of the opposition.

The ongoing war in Ukraine war is the first time in which a well-equipped special operations force has had to conduct ongoing, high-intensity combat operations against a conventional, well-equipped, well-armed adversary.

General Fenton’s view is shared by European and NATO SOF, particularly those nations close to Russia’s borders, including Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Poland, who are taking note of the way their Ukrainian brethren are operating – how they are being deployed, the tactics they are using, the countermeasures both they and the enemy are using.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter