In a talk with Tucker Carlson, Putin uttered sentences about the past. I will explain how Putin is wrong about everything, but first I have to make a point about why he is wrong about everything. By how I mean his errors about past events. By why I mean the horror inherent in the kind of story he is telling. It brings war, genocide, and fascism.

Putin has read about various realms in the past. By calling them “Russia,” he claims their territories for the Russian Federation he rules today.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Such nonsense brings war. On Putin’s logic, leaders anywhere can make endless claims to territory based on various interpretations of the past. That undoes the entire international order, based as it is upon legal borders between sovereign states.

Carlson asked Putin why he must invade Ukraine, and the myth of eternal Russia was the answer.

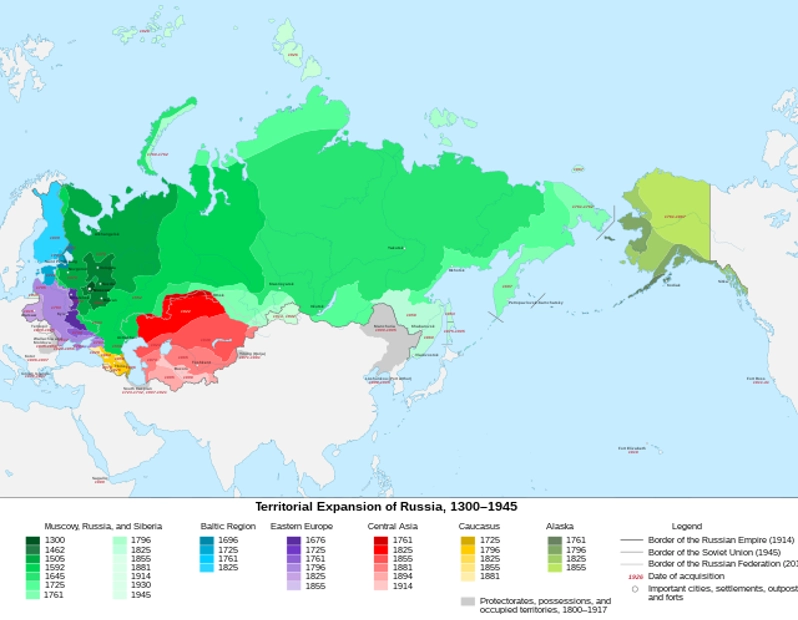

In his conversation with Carlson, Putin focused on the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries. Moscow did not exist then. So even if we could perform the wishful time travel that Putin wants, and turn the clock back to 988, it could not lead us to a country with a capital in Moscow. Most of Russia’s present territory is in Siberia. Europeans did not control those Asian territories back then. On Putin’s logic, Russia has no claim today to the territories from which it extracts its natural gas and oil. Other countries would, and Russia’s national minorities would.

Putin provides various dates to make various claims. Anyone can do that about any territory. So the first implication of Putin’s view is that no borders are legitimate, including the borders of your own country. Everything is up for grabs, since everyone can have a story. Carlson asked Putin why he must invade Ukraine, and the myth of eternal Russia was the answer.

Russia May Tap $300B in Frozen Assets to Rebuild Ukraine – With a Catch

The second problem, after war, is genocide. After you decide a country in the deep past is also somehow your country now, you then insist that the only true history is whatever seems to prove you right. The experiences of people who actually lived in the past and live in the present are “artificial” (to use one of Putin’s favorite words).

In the interview, and in other speeches during the war, Putin depends on a false distinction between natural nations and artificial nations. Natural nations have a right to exist, artificial ones do not.

But there are no natural nations. All nations are made. The Russia of tomorrow is made by the actions of Russians today. If Russians fight a lawless war of destruction in Ukraine, that makes them a different people than they might have been. This is more important than anything that happened centuries ago. When a nation is called “artificial,” this is justification for genocide. Genocidal language does not refer to the past; it changes the future.

Everyone who does not fit Putin’s neat story (Russia is eternal, so Russians can do whatever they want) has to be removed, first from the narrative of the past, and then from those counted as human in present. On Putin’s logic, it does not matter what people believe or how people understand their own past. It is he who decides which souls are bound to which other souls. Other views have no place in nature, because they arose from events which (in his story) should never have happened. His view must govern the past, which requires violence in the present: genocide.

Silver coin from Kyivan Rus with Volodymyr the Great and a tryzub, Ukraine’s national symbol.

If there are people who say that Ukraine is real, they must be destroyed. That has been the logic of Russia’s mass murder from the start. Putin expected Ukraine to fall in a few days because he thought he needed to eliminate a few Ukrainians in an artificial elite. The more Ukrainians there turned out to be, the more people had to be killed. The same holds for physical expressions of Ukrainian culture. Russia has destroyed thousands of Ukrainian schools. Everywhere Russian troops reach, they burn Ukrainian books.

The third problem is a fascism expressed as victimhood. Putin is the dictator of the largest country in the world and personally controls tens and more likely hundreds of billions of dollars. And yet in his story he is a longwinded victim, because not everyone agrees with him. Russia is a victim because Russians can tell a story about how they need to fight a genocidal war, and not everyone agrees. Ukrainians are the aggressors, because they do not agree that they and their country do not exist.

Indeed, says Putin, Ukrainians are “Nazis,” a word that in his mouth just means “people who refuse to accept that Russians are pure no matter what we do.” This is a victim claim: if the Ukrainians are “Nazis,” then Russians – even though they started the war and have killed tens of thousands of people and kidnapped tens of thousands of children and carry out war crimes every single day – must be the righteous sufferers.

Most of what Putin says about the past is ludicrous; but even had he said some true things, that would not justify destroying the international order, invading neighbors, and committing genocide.

This is how myth matters. If all the wrong in the past was done by others, as Putin says, then all the wrong in the present must be done by others. Putin’s story divides good and evil perfectly. Russia is always right, others are always wrong. Russians can behave like Nazis while calling others “Nazis” and all is well. Russia is a people with a special purpose, resisted by conspiracies. Putin’s war has been fought with fascist slogans and by fascist means, with mass propaganda and mass mobilization.

Just as there are three why problems (war, genocide, fascism) there are three how problems. Putin leaves things out before his narrative begins, gets things wrong during his narrative, and leaves things out as his narrative ends.

I’d almost rather leave it at the why. As soon as I get into the how, and start correcting the factual errors, it’s as though I am endorsing the overall logic. So just to make this clear: even were Putin a decent historian, that would not mean that he could (legally, morally) claim territory on the basis of correct things he said about the past. Real historians, as you might have noticed, do not actually have that power. Most of what Putin says about the past is ludicrous; but even had he said some true things, that would not justify destroying the international order, invading neighbors, and committing genocide.

Geography of archaeological sites of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in Ukraine (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE). Published in the Encyclopedia of Trypillian Civilization.

Before even Kyivan Rus existed

Aside from being dangerous and erroneous, what Putin says about the Ukrainian past is boring. He leaves out important things about the history of the lands that are now Ukraine. Thousands of years before Putin begins to get everything wrong, world-historical trends emerge from lands that are now Ukraine. Deep in the Bronze Age, about 6,000 years ago, there were large settlements (“mega-cities”) in what is now Ukraine. About 5,000 years ago, the people who built those cities were displaced by pastoralists who had domesticated the horse. Those people brought from the steppe with the beginnings of languages now spoken by about half the people of the world. About 2,500 years ago, Scythians from what is now southern Ukraine encountered Greeks, supplying them with some of their best stories (including those of Amazons, female Scythian warriors). Scythia, or the southern coast of what is now Ukraine, fed Athens during the time of its greatest flowering, and Greeks lived in cities on what is now the southern Ukrainian coast.

One could go on from there to the Sarmatians, the Goths, and the Khazars. The lands of what is now Ukraine may very well have been the first European territories inhabited by humans; however that may be, they have been inhabited, often by hugely influential peoples, for about 37,000 years. If it were truly the case that one could claim territory today on the basis of who was there first, Russia would have a weak claim.

The real Rus, not Putin’s fairy tale

All of Putin’s utterances about the period he finds interesting, beginning in the ninth century AD, are wrong. He starts up Tucker Carlson with a pleasant tale about how people in Novgorod “invited” a “Varangian prince” to rule them. History is a rougher business than that. This was the Viking age. A Viking slaving company known as “Rus” was finding its way down the Dnipro River to exchange its Slavic slaves for silver. Eventually those Vikings made of Kyiv, at the time a Khazar fort, their main trading post and port and later their capital.

In the interview, Putin invites Carlson to believe that this was a “centralized state” with “one and the same language.” This is just ignorance. It was a medieval kingdom, not a state in our sense. It was certainly not centralized. That is a fantasy. Nor did it have a single language. The Viking and post-Viking rulers had three names: their Scandinavian ones, with time their local (Slavic) ones, and after conversion their baptismal ones. There was a Slavic language at the time and place, spoken by much of the population and eventually by the rulers, but it was not modern Russian or Russian of any description. Some of the language of politics was from the Khazars. There were Jews in ancient Kyiv who knew Hebrew and Slavic. There were plenty of other languages spoken as well, from several different linguistic families.

Were Putin serious that the past determines the present, he should say that the territories of that medieval Viking state, Kyivan Rus – much of Ukraine, all of Belarus, some of northeastern Russia by today’s boundaries – should belong to Sweden, or Denmark, or Norway, or perhaps Finland. The creation of Kyivan Rus was one of several spectacular examples of Viking state-building around the year 1000. This broad history includes Sicily, Normandy (and so indirectly England) as well as the Scandinavian kingdoms. Sometimes Viking ambition includes several of these states at once, as when Harald Hardrada, who had served the army of Kyivan Rus, took up the kingship in Norway and invaded England. Putin speaks of Yaroslav the Wise; in an Icelandic source that fascinating ruler figures as Jarisleif the Lame. He was widely known in the Europe of the day (but not in Moscow, which did not exist).

Yaroslav the Wise on a Ukrainian banknote

Then the Mongols arrive in Kyiv, in 1240. This is an awkward moment for Putin, since it reveals the problem with his reasoning. If the Mongols destroyed Kyivan Rus in about 1240, why not pick then as the date that is forever valid? Why is that any worse than the earlier and later dates Putin chooses? Why does Mongolia not have a claim on Kyiv, and for that matter on Russia? On Putin’s logic, it must. Putin skips hastily over this awkwardness to the (false) claim that “northern cities preserved some of their sovereignty.” He means that Moscow preserved the sovereignty of Kyivan Rus under Mongol rule. But Moscow did not exist. By the time the Mongols invaded, there was a settlement on the site, but the Mongols burned it down. When Moscow was rebuilt, it was as a site of tribute collection for the Mongol overlords. That is the founding moment of the state centered in Moscow. Why then does today’s Moscow not now belong to Mongolia?

In the English transcript of the interview provided by the office of the president of the Russian Federation, which I am using, Putin keeps saying “Russian.” This is not the kind of thing one can expect Carlson to notice, but it is an error every time Putin does it, at least for most of the centuries he is talking about. Kyivan Rus was in no way “Russia.” It was named after Vikings who became rulers. That name “Rus” came to be associated with the land and its people and with Christianity. But “Russia” as Putin is using it, when it refers to anything specific, is an empire founded in St. Petersburg (a city that did not exist at the time of Kyivan Rus) in 1721. That Russian Empire was named “Russian” precisely as a claim to lands and to history. But just because Peter the Great made a clever public relations decision half a millennium after the Mongols took Kyiv does not mean that there was a Russia when the Mongols arrived. There was not.

Whereas the Russian Empire…

The Russian Empire that arose from Moscow was a very important state. But even the Russian Empire (1721-1917) was not a Russia in the way Putin wants. Most of its territory was in Asia. There was no Russian national consciousness among its peoples on most of its territories for most of its existence. Most of its population did not speak Russian. Its ruling class was largely German, Polish, and Swedish. Catherine the Great, the empress Putin venerates, was a German princess who came to power after the murder of her husband, who was a German prince. (Much the same can be said, incidentally, for the Soviet elite. It is only with Boris Yeltsin and his chosen successor Putin that we have before us unambiguous Russians durably ruling in a country called Russia. It is perhaps this very novelty and uncertainty that stands behind a view of the past that is at once naive and cynical. Russia’s nationhood is postmodern, and it shows.)

In moving from the Middle Ages to the present, Putin then commits a huge error of omission. He refers very briefly to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and only to tell Carlson that they oppressed “Russians.” The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were the largest countries in Europe. It was Lithuania that inherited most of the lands of old Rus, at around the time its rulers became kings of Poland. Poland-Lithuania included Kyiv for more than 300 years – longer than Kyiv was part of Kyivan Rus, longer than Kyiv was ever part of the Russian Empire. Much of the impressive political culture of Kyiv shifted to Vilnius. Again, by Putin’s own logic, the lands that are now Ukraine should therefore be claimed by today’s Lithuania or today’s Poland.

Just because Peter the Great made a clever public relations decision half a millennium after the Mongols took Kyiv does not mean that there was a Russia when the Mongols arrived.

A great deal happened during those 300 years: the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Counter-reformation. All of these marked Ukraine (as it was now called) and made it different from a Muscovite state largely untouched by those trends. Ukrainian Cossacks rebelled against Polish rule, on the basis of an understanding of a legal duty of rulers to subjects that existed in Poland-Lithuania but not in Muscovy. When Ukrainian Cossacks rebelled against Polish rule, they were led by a man educated by Jesuits who knew Ukrainian, Polish, and Latin but did not know Russian, and who used translators to communicate with Muscovites. The Cossacks did cooperate with Moscow after they lost their Crimean Tatar allies, and this did lead to wars that ruined Poland-Lithuania and allowed Muscovy to expand westward.

But Putin is wrong that the agreement signed between Cossacks and Muscovy in 1654 was some kind of eternal soul-binding of Ukrainians to Russians. Like many things he thinks, this was Soviet propaganda with a specific purpose. Khrushchev’s regime made this claim to explain why Ukraine, which everyone accepted was a nation, was nevertheless bound forever to Russia inside the USSR. It was based on political need, not historical fact. There is something pathetic about someone as versed in lying as Putin actually believing the lies he was told when he was young.

Starved peasants on a street in Kharkiv, 1933. In “Famine in the Soviet Ukraine, 1932–1933: a memorial exhibition,” Harvard University.

Language, famine and the Nazis were right

Putin makes a mistake about the Ukrainian language, over and over, that is typical of imperial deafness. It is true that Ukrainians today can speak Russian (although many also, for understandable reasons, refuse to do so) as well as Ukrainian. When they encountered Russians, until very recently, Ukrainians would switch to Russian. This courtesy gave Russians the impression that Ukrainian was just a dialect of Russian or that Ukrainian did not exist. The simple truth is that Ukrainians know Russian because they learned it. Russians do not know Ukrainian because they do not learn it. Russian soldiers right now, two years into the war, persist in calling the Ukrainian they hear on radio intercepts “Polish” because they are unable to grasp the obvious: that there is a Ukrainian language, and they do not understand it. Putin’s notion that there is no Ukrainian language is like his idea that there is no Ukrainian country or Ukrainian people: it is genocidal, because only mass killing can make it true. And of course one thing that is clear from this interview is that Putin takes it for granted that killing any number of people is preferable to admitting a mistake. Ideas matter. It is because he is wrong about everything that he must kill.

Putin perhaps comes closest to realizing his own problem when he talks about the 20th century and the creation of the Soviet Union (and its Ukrainian republic). Putin is sure that there was no Ukraine in history, and therefore he must present Lenin and Stalin as fools, because they acted as if Ukraine were real. Now, Lenin and Stalin were many things, but they were not fools. Putin says that they acted for “inexplicable” or “unknown” reasons in creating a Ukrainian republic and applying (in the 1920s) policies consistent with the existence of Ukrainian language and culture. Lenin and Stalin did this because they knew, from their own personal experience, that there was a Ukrainian national movement. They did not wish for this to be true; they were simply confronted with it at every step. They knew that there had been a Ukrainian national movement in the Russian Empire. They knew that Ukrainians had tried to found states after the Bolshevik Revolution. They knew that they had defeated these attempts after years of extreme violence, and that something else would have to be done over the long run.

Putin calls the Soviet Union “Russia” and tells Carlson that the Soviet Union was just another name for Russia. Here he is simply wrong. Russia was a part of the Soviet Union. About half the population were not Russians. Ukraine and other republics were subject to russification policies, but no Soviet leader claimed (as Putin does) that these republics were an element of Russia. The Soviet Union took the form it did, as a nominal federation of national republics, because Lenin, Stalin, and other Bolsheviks knew, more than 100 years ago, that they had to reckon with Ukraine. They created a Soviet Union with national republics because they knew they had to make some compromise with political reality, above all the reality of Ukraine.

When Soviet policy turned against Ukrainians in the early 1930s, this was because Stalin was afraid of losing Ukraine as a result of his own disastrous policies, not because he thought Ukraine did not exist. He was right to believe that Ukrainian peasants would resist his policy of seizing their land; many of them did, so long as they could. He and other members of the politburo engineered a political famine in Ukraine on the logic that Ukrainians in particular should be punished for the failures of Stalin’s own policy. Putin ignores these events completely; but they were a lived and unforgettable reality for the survivors. The generational memory of what Ukrainians call the Holodomor is one way Ukrainians today differ from Russians.

Putin talks about the Second World War as if it were a Russian ethnic struggle, but it was a Soviet struggle. And the Soviet peoples who suffered the most, after the Jews, were the Belarusians and the Ukrainians. More Ukrainian civilians were killed under German occupation than Russian civilians. Ukrainian soldiers were overrepresented in the Red Army that defeated the Germans on the eastern front. These are among the important facts of contemporary history that Putin simply passes over. Or he makes things up: like his claim that he lectured the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, about Zelensky’s father, who was in the Red Army. It was Zelensky’s grandfather. His great-grandfather and three great-uncles were murdered in the Holocaust. Putin has lost track of the generations and lost sight of what mattered and to whom.

One thing that is clear from this interview is that Putin takes it for granted that killing any number of people is preferable to admitting a mistake.

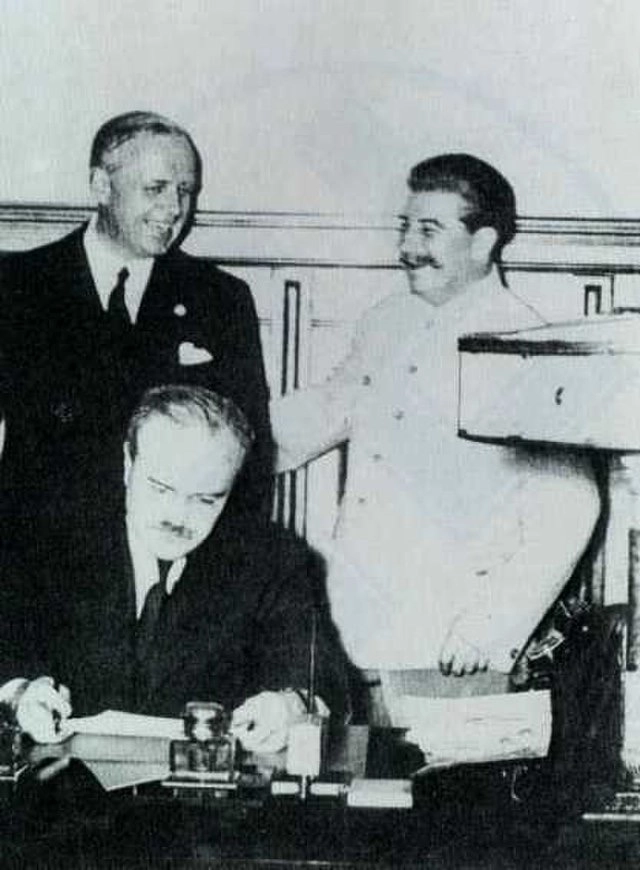

What Putin has to say about the Second World War is that Hitler was right. For a decade now, Putin has been justifying the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the 1939 alliance between Stalin and Hitler than began the Second World War. His argument at the beginning was that the Soviet choice to join Nazi Germany in the invasion of Poland was just the sort of thing everyone was doing. But it is hard to see how Hitler could have started his war had the Soviets simply held to the non-aggression pact they had earlier signed with Poland.

Now Putin has taken a further step, saying that Poland had (somehow) both collaborated with Germany too much and simultaneously not collaborated enough and thereby brought the war on itself. Putin wants to say that Poland collaborated with Germany to distract from the basic fact that the Soviet Union entered the Second World War as a German ally. Warsaw refused to fight on Berlin’s side in 1939; Moscow agreed. Putin blames the war on Poland because his own approach to borders and history in 2024 is like Hitler’s in 1939. Putin’s “historical” argument about Ukraine is consistent with Nazi propaganda about Poland, right down to the business about “artificial” states and peoples with no historical right to exist.

German ambassador Joachim von Ribbentrop (left) and Soviet dictator Stalin laugh as Vyacheslav Molotov signs the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty on Sept. 28, 1939.

Putin’s claim that the Ukrainians are the actual Nazis isn’t even framed as history. He just says it. This sort of claim is itself fascist: it rests on a domestic politics of us-and-them, where Russians are told that they are always innocent; and an international propaganda campaign meant to confuse by name-calling.

Ukraine has much less of a problem with the far right than does Russia, or for that matter than the United States, or pretty much any other European country you care to name. Ukrainians elected a Jewish president by more than 70 percent of the ballot, without his Jewishness being much of an issue. That would be a challenge elsewhere. The Ukrainian minister of defense is a Crimean Tatar (and a Muslim). The commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian armed forces was born in Soviet Russia to Russian parents. Ukraine manages a degree of diversity, even in wartime, that reflects its fascinating history, a past that cannot really be described in a text like this, one which has to have to narrow purpose of showing how and why Putin is wrong.

Putin’s kind of story leads to war, genocide, and fascism.

Putin has been making the argument of his interview since 2010; his myth about the past is a major subject of my book The Road to Unfreedom, which charts its origins and defines its consequences at greater length. Putin’s kind of story leads to war, genocide, and fascism. It also, though this might seem like a much smaller wound, makes history harder to practice.

When stories like his are successful, people in other countries think that they too need an account of eternal innocence to justify the awfulness of the everyday. And historians can be pulled into the vortex, spending their times answering lies rather than doing their research. My own positive version of Ukrainian history is available in the public lecture series available here.

I close this essay with bibliography to emphasize that history is about researching, considering, and making interesting and defensible arguments. Ukrainian historians keep doing this, even during the war. The last item by Hrytsak, for example, has just been released and deserves a wide readership.

Simon Franklin and Jonathan Shepard, Emergence of Rus 750-1200, London: Routledge, 1996.

Christian Raffensperger, The Kingdom of Rus, Arc Humanities Press, 2017.

Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996

Ivan L. Rudnytsky, Essays in Modern Ukrainian History, Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1987.

Tatiana Tairova Yakovleva, Ivan Mazepa and the Russian Empire, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020.

Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Barbara Skinner, The Western Front of the Eastern Church, Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Serhiy Bilenky, Laboratory of Modernity: Ukraine Between Empire and Nation, 1772-1914, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023.

Matthew D. Pauly, Breaking the Tongue: Language, Education, and State Power in Soviet Ukraine, 1923-1934, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014

Golfo Alexopoulos, Illness and Inhumanity in the Gulag, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, New York: Doubleday, 2017.

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Mayhill Fowler, Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine, University of Toronto Press, 2023.

Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: The Birth of a Modern Nation, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Myroslav Marynovych, The Universe Behind Barbed Wire: Memoirs of a Ukrainian Soviet Dissident, Rochester University Press, 2022.

Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America, New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018.

Stanislav Aseev, The Torture Camp on Paradise Street, Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2023.

Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe, New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ukraine: The Forging of a Nation, New York: Public Affairs, 2024.

Reprinted from the author’s blog: “Thinking about…” See the original here.

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter