“When I go to work, I understand that I may not return,” says Mykhailo, a power station worker. The plant where he works has been hit by missiles ten times since October when Russia launched its campaign to try to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

“Any normal person would be scared,” he adds. “I have a family and an eight-year-old child.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

“They call all the time, worrying about me.”

They may be far from the trenches, but Mykhailo and his colleagues are on another front line of the war, battling to keep Ukraine’s power supply running in unimaginable circumstances.

A crater five meters in diameter left by a Russian missile near the power plant. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

A crater five meters in diameter left by a Russian missile near the power plant. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Some 1,000 people work at the DTEK power plant station and, when the air raid sirens sound – which can happen up to five times per day – most head to the bomb shelters. But a core team of three or four people must stay to run what is known as the blocking shield – the central control point of the station that is vital to keep the plant functioning.

“When there’s a notification about the launch of missiles, that the missiles have entered Ukraine’s airspace, you understand that they are most likely flying here,” says Mykhailo.

“We have helmets and bulletproof vests, but this is unlikely to help us survive a missile hit.”

Zelensky Seeks More Sanctions as Latest Russian Strikes Kill 14

Several of the station’s employees have been nominated for state awards. Kyiv Post visited them to hear their stories in their own words, which are set out below.

For security reasons, the plant’s name, location, and the last names of its workers have been withheld.

The power plant’s switchgear, bombed by a Russian missile. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

The power plant’s switchgear, bombed by a Russian missile. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Ihor, chief specialist at the electrical department

"We are now working seven days a week. On days when the missile attacks take place, my colleagues arrive at the station to help minimize the consequences. The equipment is complex and requires constant human attention. A missile could hit the same place twice.

"During one of the missile attacks, I was at the plant when there was an explosion nearby. The windows shattered and everything was blown off my desk. First, I looked at my hands – there was no blood. I ran my hands over my face and looked again – there was no blood. Then I immediately went to check on my co-workers.

"Usually, I ask my family not to call me because the work requires concentration. However, I called them immediately after the attacks to say: 'My hands and feet are intact, and everything is fine.'"

Power plant transformer damaged by a Russian missile attack. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Power plant transformer damaged by a Russian missile attack. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

"These missile attacks have caused many irreparable losses to the station. We lack equipment. I’m inventing creative new technical solutions to ensure the station’s vital activity. Restoring the station after the shelling takes a week to a month. If a city district remains without electricity after the shelling, we usually restore the power supply within a day, including repairing the heat supply to ensure heating systems work.

"We work around the clock. The director of the plant has lived here for couple of months and even slept here at night."

Mykhailo, blocking shield operator, station control point

"Four of us work here in the operation control room. We don’t go to the shelter during the alarm and remain at our workplaces. If the power station’s operators were to leave their workplaces, the whole country would shut down.

"When there’s a notification about the launch of missiles, that the missiles have entered Ukraine’s airspace, we understand that these missiles are most likely flying here. We have the helmets and bulletproof vests, but this unlikely to help us survive a missile attack. Many of our fighters are at the front line, risking their lives now. This is also the front line to some extent."

A burnt transformer at the power plant following a Russian attack. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

A burnt transformer at the power plant following a Russian attack. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

"Since the beginning of the war, it has become scarier to go to work. When I go to work (a shift at a thermal power plant during the war lasts 12 hours) I understand that I may not return. Any normal person would be scared. I have a family and an eight-year-old child. They call all the time, worrying about me.

"We are all friends on the team. We joke, encourage each other and laugh when we’re scared. If you dwell on all this, then it becomes hard to endure emotionally, so we save ourselves with humor.

"For example, our boss jokes and says: 'It’s boring. It’s been a long time since a Russian missile has come our way.' Everyone is outraged, and he walks around laughing."

Volodymyr, block shield operator, station control room

"There’s a lot of tension and a heavy workload because of insufficient staff – many refuse to work here because of the risks. It’s mainly the elderly and young who are left. The work schedule and the regime have both increased. It’s not pleasant to sit with tension during the air alarm. When you see a rocket exploding outside the window, it’s scary. We can’t go to the shelter – it will create an emergency and leave people without light.

"Although, what is there to be afraid of? Ten rockets have already hit the station. The first time everyone was in a state of shock. Now we’re used to it.

"Of course, humor helps. We need to defuse the atmosphere so we send funny pictures and memes in our group chat. I sent a funny picture a moment ago.

"We don’t joke about politics though. We don’t want to think about it again. Sometimes we joke about the management. I’m not afraid, because not many people want to sit at this desk. Of course, my boss doesn’t always appreciate my humor."

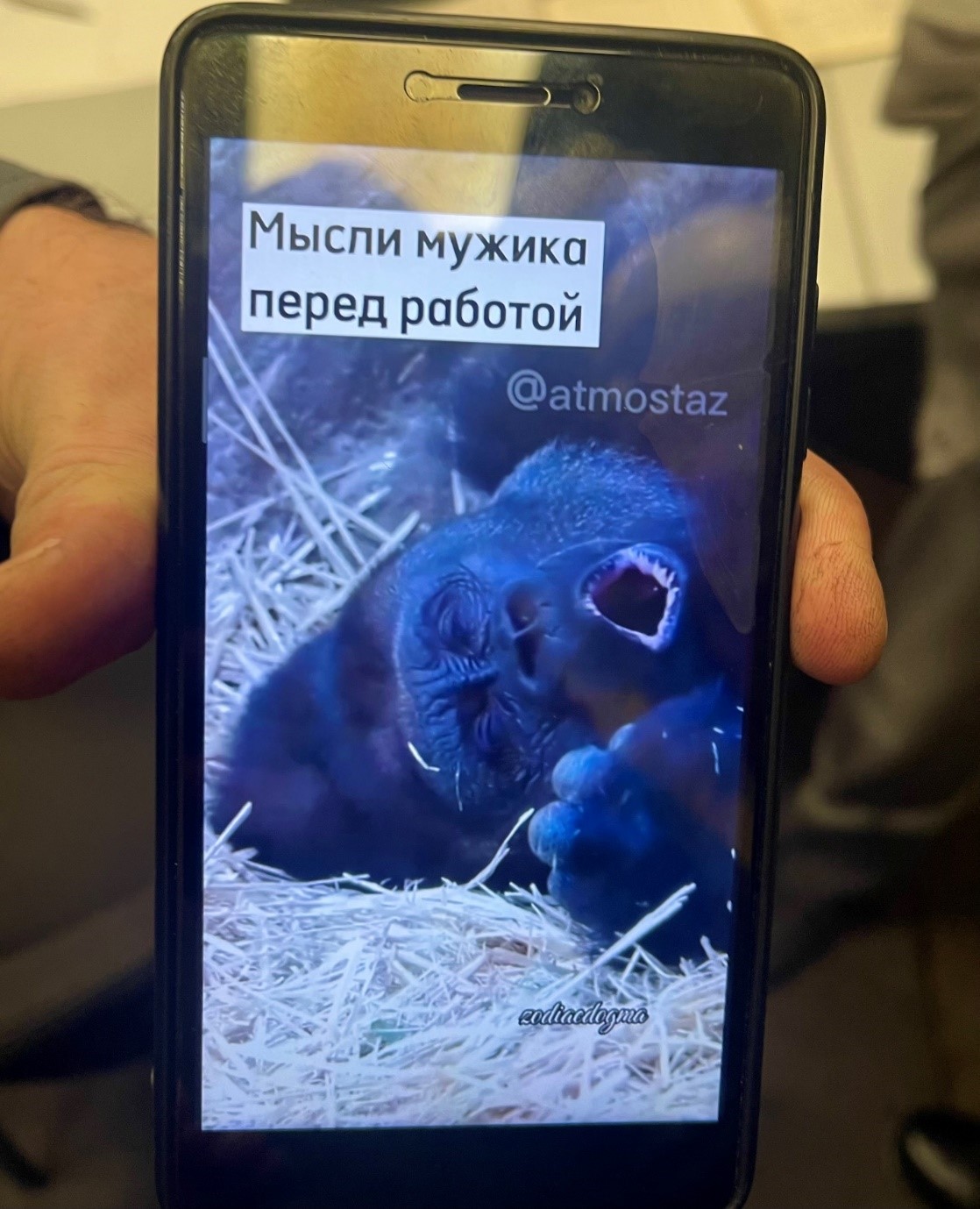

“Thoughts of a man before work.” A meme from Volodymyr’s phone. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

“Thoughts of a man before work.” A meme from Volodymyr’s phone. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

"Relatives, of course, are afraid and worried. They call every five minutes. It’s easier to turn off the phone and work."

Dmytro, head of the operations team, station control room.

"We must promptly respond to the aftermath of any missile destruction, so we are not allowed to go to the shelter. I have five people subordinated to me and we have friendly relations. It’s more official with senior managers. They don’t like jokes.

"When there’s an alarm, we monitor what’s flying and where. That’s all we can do. Russians usually shoot at the station once a week. Once a rocket hit 50 meters from our control room. There was nothing but deafening noise, dust, and the equipment was damaged.

"Also, there was no rocket whistle, just an explosive cloud and darkness. At the moment of the explosion, fire and black smoke rose for two seconds, and then it got lighter. We were all silent for some time, just looking at the damage caused by the rocket to the station."

Damaged power plant equipment. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Damaged power plant equipment. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

"I don’t believe that ordinary Russians are involved in this. There is propaganda in Russia. Maybe they don’t understand what’s happening.

"We have hope for the future joining the European Union. In the EU, there’s a completely different assessment of such work and better pay. We may get to EU someday."

Station equipment damaged by an explosion. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Station equipment damaged by an explosion. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter