Note from the Editors. The following is the text of a presentation delivered by Kyiv Post’s Chief Editor Bohdan Nahaylo at a Ukrainian Historical Encounters Series Special Event entitled: “Russian-Ukrainian ‘Memory Wars’ in Western Academia and Media” held on Sept.16, 2023, at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York City during a panel discussion on “RU-UA Memory Wars in the Realms of Print Media, Broadcast Media and the Internet.” Click here for Part 1.

From the historical background towards the present

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

After independence was finally achieved, during the next 30 years things did not go the way that many would have preferred.

Independent Ukraine was plagued with a host of gaps and disabilities inherited from the Soviet period. The injuries and damaged psyche proved debilitating. Consequently, the new state did not develop and mature as the opportunity warranted. Time was wasted, opportunities squandered, and drift instead of dynamism with clear goals set in.

A low level of political culture, governance and accountability persisted. Oligarchs and their like emerged and grabbed what they could. Cynical leadership and a confused population not being induced to act as responsible citizens were hardly what Ukraine needed.

There were internal demons to be overcome in the historical sphere, where the search for historical objectivity and truth was called for.

This cocktail of shortsightedness, greed and corruption came to permeate the media, the approach to history, and especially the relationship with Russia.

On the one hand – the official level – it meant playing along, opportunistically, with Russia, exploiting economic advantages at the cost of reasserting Ukraine’s distinct history and self-identification. The Russian imperial narrative and legacy were hardly challenged, including the role of Moscow’s major remaining ideological asset in Ukraine, the Russian Orthodox Church. A “laissez-faire” attitude in this realm was tolerated, if not implicitly promoted, by those at the intertwined helms of politics and business.

On the other hand, the unofficial approach saw nationally minded civil society and braver, more outspoken historians seeking to retrieve the nation’s history and cultural figures appropriated by Russia and to promote not only de-Sovietization, but also de-Russification.

Confronting the past

Certainly, there were internal demons to be overcome in the historical sphere, where the search for historical objectivity and truth was called for. Not all historians trained in the Soviet period and its aftermath were up to it; and many of the younger ones were influenced by their mentors, paymasters or political gurus. Inflated patriotism, so often based on emotion and romanticism rather than sound historical knowledge, tended to degenerate into declarative forms of blinkered ultra-nationalism exploited by opportunistic and manipulative political forces.

Not surprisingly, there were difficulties in sensitive spheres.

For instance, facing up to how the Holocaust had actually taken place on Ukrainian territory. What had been the role of the Ukrainians when Jews were being systematically slaughtered by the Nazis? Passive bystanders, active participants, or victims themselves? These questions were not really addressed, exposing Ukrainians to continuing accusations from the outside, while for those brave enough to pose frank questions from the inside there was disdain.

Or, in relations with the Poles – by no means an easy subject to handle. Whereas Ukrainians had been developing their own broader historical narrative and pointing the finger at the Poles, there was no way to get around the painful question of what occurred in Volhynia in 1943, when brutal ethnic cleansing was carried out in a desperate struggle over the future control of this territory. The Poles blame the Ukrainians of mass, neo-genocidal crimes, while the latter have sought to defend the actions of the previous generation as a form of self-defense against colonization.

But on the whole, despite the stumbling blocks, considerable progress was eventually made by historians in both countries to find common ground for understanding and cooperation – something that was not seen in the case of Russia’s historians.

What had been the role of the Ukrainians in the Holocaust? Passive bystanders, active participants, or victims themselves? These questions were not really addressed…

The history of the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) and UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), and especially of some of their leaders, such as Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevych, Vasyl Kuk, and others, continue to pose problems. Bandera, for example, was glorified uncritically by those eager to find a Ukrainian hero to embody Ukraine’s fight for freedom and vilified and condemned mechanically by those opposed to Ukrainian nationalism. But few bothered to search for the truth and present him and the period he represented objectively – the good, bad and the ugly. The lack of balanced approaches only perpetuated division and confusion.

Ukraine’s long interconnection with the Turkic, Muslim world to the south was rarely acknowledged or examined. Even the Crimean Tatars, who were allowed to return to Crimea in the early 1990s from the places in Central Asia where they had been deported by Stalin, were seldom given the political, cultural and economic support that they deserved until quite late in the day.

Then there is Jan. 22, 1918 – the date of the proclamation of Ukraine’s independence by Ukraine’s first modern free parliament, the Central Rada. Why was this date and its significance obscured after 1991 under consecutive presidents and the focus kept only on Aug. 24, 1991? Just because the communist majority in the parliament at that time had insisted it be so as a compromise with the national democratic minority in the hall promoting independence?

Fast forward to other issues – the Poroshenko period after the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity, when Ukraine was forced to defend itself against Russian aggression in Crimea and the Donbas. Recall the last-minute attempts in 2018-19 by the incumbent “patriotic” president, Petro Poroshenko, increasingly beleaguered because of charges of corruption and cynicism and trailing in the polls as a new presidential election approached, to play on the themes of “Army, Faith, Language,” and how it ended – 73 percent of Ukraine’s voters rejecting him.

Ukrainian journalism’s growing pains

All of this put journalism to the test. Not surprisingly, many journalists, including some of the most capable, became servants of the oligarchs who controlled their TV channels or newspapers and paid their salaries. The Savik Shuster political TV show became the prized showpiece for shaping political opinion as per the paymasters’ wishes and while masquerading as freedom of expression in action made a travesty of genuine journalism.

No serious attempt, with the proper funding and staffing, was made to establish a Ukrainian version of the BBC, and independent and reliable source of information both for the domestic public and the outside world – something similar to what Poland has done by creating it’s TVP World channel with its impressive English-language service. Instead, I myself witnessed the shameful underfunding and decay at what had been in Soviet times the secretive but well-equipped state radio broadcasting center on Khreshchatyk 26, a stone’s throw from Independence Square.

Indeed, with few exceptions, Ukraine’s journalism remained introverted and parochial and little effort was made to make the country’s concerns known externally.

It was left largely to publicists of Ukrainian origin, representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora, to attempt to interest the outside world in Ukraine, its development, and explain the challenges it faced. Important roles in this regard were played by The Ukrainian Weekly published in the USA since 1933, and the English-language newspaper Kyiv Post which was launched in Kyiv in 1995.

Meanwhile, there was also the huge problem of the pro-Russian Trojan horses within Ukrainian society, the body politic, religious life and the media – the de facto fifth columnists who promoted Russian narratives, whether explicitly or implicitly. Invoking democratic principles and well financed by their patrons, they remained free to carry out their insidious mission.

So yes, there was freedom of the press. And even martyrs for this cause as in the case of the legendary Georgian-Ukrainian journalist Georgiy Gongadze who was murdered in 2000 during the presidency of Leonid Kuchma apparently on “orders from above.” Or later, the Belarusian Pavel Sheremet, an opponent of Minsk’s despot Aleksandr Lukashenko who while working for the Ukrainian media was blown up in his car in the center of Kyiv in 2016. But liberty to say anything and everything, disregarding the fact that Ukraine was under direct or indirect siege by Russia – politically, economically and culturally – was hardly conducive for the purposes of building a sovereign, inclusive, European, democratic state and helping it to find its bearings.

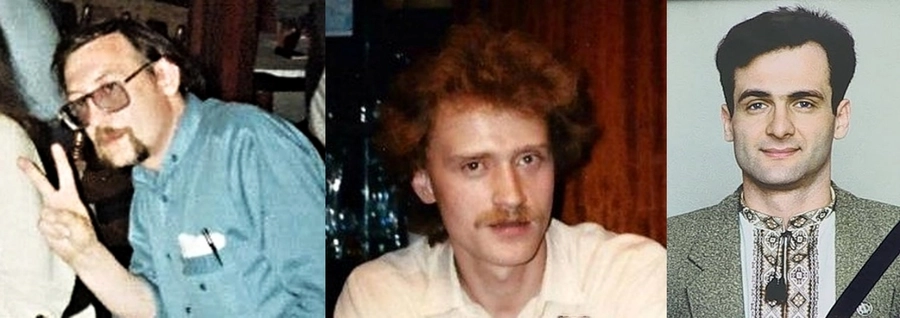

Three of the pioneers of the independent press in early post-independence Ukraine. From left to right: Serhii Naboka, Oleksandr Krivenko and Georgiy Gongadze.

Bewildered citizens

Without the application of the principles of defensive democracy to protect the sovereignty of a democratic Ukrainian state, many citizens were left bewildered as to the choice between the democratic West (encompassing the EU and NATO), and the “brotherly” Euro-Asiatic CIS led by the inherently imperialistic and despotic Russian colossus with its vast energy resources and tempting incentives for corrupt practices.

Fortunately, despite the failure to capitalize on the surge of attention that Ukrainians received temporarily during the Orange Revolution in late November 2004 to January 2005, a decade later, during the Revolution of Dignity, there was another chance to be heard and to elicit international support.

Despite the heroism shown on the Maidan and the new battlefields in the Donbas, along with the efforts of civil society and the diaspora, Ukraine’s leaders, diplomats and journalists did not manage to convey the nation’s history and existential plight to the outside world as effectively as was called for.

Whatever the sympathy for Ukraine after Russia’s seizure of Crimea and part of eastern Ukraine, with Russian propaganda and fake news working overtime, the distinction between Russia and Ukraine as distinct separate nations remained blurred. Moreover, dependence on Russian energy supplies and the fear of possible military confrontation also restrained key Western leaders in their support for Ukraine.

But there was a silver lining. In the outside world the Ukrainian case was eloquently taken up by a host of distinguished scholars, analysts and journalists who during the last decade have done so much to inform the international public about Ukraine, its history and current predicament. They include Timothy Snyder, Ann Applebaum, Anders Aslund, Diane Francis, Timothy Ash, Timothy Garton Ash, Peter Dickinson and Michael Bociurkiw. Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy has excelled in this realm (could Ukraine’s pre-eminent historian from more than a century earlier, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, or for that matter even Orest Subtelny, ever have imagined the history of Ukraine attracting so much attention internationally?). Likewise, the Ukrainian writer of Russian origin Andrei Kurkov has shone internationally on the literary scene.

Today’s media landscape

But what of the quality of Ukraine’s media? Undoubtedly there are a number of reliable news outlets, but few of which have an impact outside of Ukraine and also effectively challenge Russia’s narratives regarding history and the war.

Many of the Ukrainian journalists I’ve met in recent years would not, in my personal opinion, qualify as serious exponents of this profession in the West. Too much editorializing on their part. Too much of me, me, me, of abusing the medium as a vehicle for self-promotion, allowing opinion to predominate over hardcore journalism and balanced enquiry and analysis.

Instead of what they or their editors or owners think, where was the concise, accurate, timely news and information serving the public interest, as opposed to certain wealthy politicians or individual egos? The “who, what, when and why” – without all the subjectivity. And where was the effort to win the sympathies and attention of the outside world with the proper level of obective, yet critical, enticing information? Why was there not a concerted state-diven effort to carry the Ukrainian narrative and news into Russia proper, which logic demanded, to present Ukraine's case with the help of Russian political refugees and offest propagandistic preparations to destroy its neighbor?

On TV and the social media this general malaise grew all the more conspicuous. Which begs questions about the way in which journalism continues to be taught and practiced in rapidly changing conditions.

Conclusion to follow in Part 3.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article stated Georgiy Gongadze was murdered in 1990. He was in fact murdered in 2000.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter