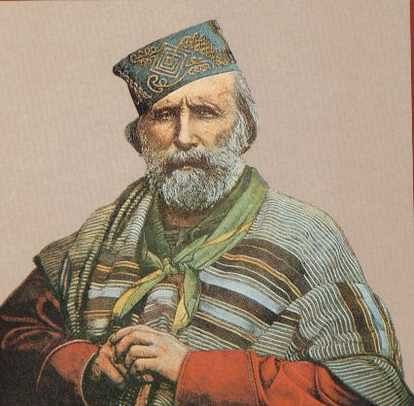

To this day, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) is the best known Italian national hero in the world. There are streets, monuments and restaurants dedicated to the “General,” who was a sort of 19th-century Italian Che Guevara. Few, however, know of the relationship that Garibaldi had with Ukraine, in particular with Odesa.

Before becoming a fighter for the freedom of peoples – not only in Italy, but also in South America – Garibaldi had embarked on a maritime career and was the captain of a merchant vessel, which plied the Marseilles-Genoa-Constantinople-Odesa route.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

In Odesa he met the local Italian community, which had built the foundations of the new port city, and – after the subsequent arrival of German, French, Greek, Russian, Polish and Jewish immigrants – maintained a sort of cultural hegemony over the city. In fact, Italian singers and musicians were at home at the Opera Theatre. In the company of these Italian artists and entrepreneurs, Captain Garibaldi was often found drinking in the cellars of the popular Grechskaya and Langeronskaya streets of the city center.

As a sailor, Garibaldi was exposed to the revolutionary ideas of his time. One time, he had French socialists on board going into exile toward Constantinople. From them he learned about the socialist theories of Henri de Saint-Simon. In some ports, he met other exiles – followers of Giuseppe Mazzini’s subversive ideas about the unification of Italy – and became passionate about the idea of fighting for the oppressed. His ship was attacked several times by Greek pirates. One of those time, as he repulsed them with weapons, he received his first light wound.

Worldwide Marches Planned This Weekend Condemning 3rd Anniversary of Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

His life then became that of a revolutionary, moving from one insurrection to another. He spent a few years in Brazil and Uruguay, where he participated in several local independence wars, achieved many military successes, and met the woman of his life: the Brazilian Anita. Garibaldi’s tireless presence in uprisings earned him the international fame of “Hero of Two Worlds.”

When Garibaldi returned to Italy to fight for Italian independence, wearing his unmistakable South American poncho and Victorian smoking cap, he was by then a commander skilled in the art of war, especially in guerrilla warfare. Garibaldi did not need to recruit an army, because wherever he was, red-shirted volunteers flocked from all over Italy and other countries, eager to fight under his leadership. Thanks to his warrior charm, donations also arrived from all over the world, especially from the English and French Masonic lodges, which had chosen him as a champion against monarchical absolutism and religious obscurantism.

In fact, he was the only Italian general capable of winning battles throughout the 19th century. In his generous fight against oppression, he even fought in France during the Prussian invasion of 1870-71. Indeed, he was the only general in the French army to defeat the German army at Dijon. However, the French do not like to remember that episode, in which an Italian humbled their military pride.

This important historical figure should be an example for the current war against the Russian invaders. If Garibaldi were still alive, he certainly would have volunteered alongside the Ukrainians, also in memory of his happy youth in Odesa.

That being said, if in the history books the hero of two worlds remains an icon of the struggle for the freedom of peoples, today he would probably be considered an international terrorist. And even the financial and military aid he received from the colonial empires of the time, England and France, would expose him to the accusation of having fought in the service of imperialism and not for Italian independence, as some opinion-makers in Italy stigmatize the armed defense of the Ukrainians.

The tragic irony of Garibaldi’s life was that, after fighting in three wars of independence and leading three insurrections against foreign domination, the new Kingdom of Italy repaid him by ceding his predominantly Italian hometown of Nice to the French emperor Napoleon III, in exchange for France’s decisive military support against the Austrians. For the poor revolutionary sailor it was a disgrace, comparable to the cession of some Ukrainian territories to Russia, which today many European pundits are hoping for in the name of a ceasefire.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter